Introduction

“They became men overnight”. A reference to young 19 year-old crewmen that had only been in the Navy for six months and rose to the occasion in the rescue operations after Voyager collided with HMAS Melbourne.

Tomorrow marks the day, 60 years ago, of the worst peace-time tragedy for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN).

Towards the end of a series of routine training exercises 20 nautical miles off Jervis Bay, the Daring class destroyer Voyager made a tragic mistake in calm conditions. It inexplicably turned towards the bow of the RAN flagship, HMAS Melbourne. Both ships collided, and Voyager was cut in half and sunk with 82 dead.

HMAS Melbourne

The RAN had three ships bearing the name HMAS Melbourne. HMAS Melbourne (II) was commissioned in 1955 and was one of six Majestic Class light fleet aircraft carriers ordered for the Royal Navy (RN) during World War II. Named initially HMS Majestic, the ship was close to launch in 1945 when the RN halted construction due to the war’s end. In 1946, the RAN was allowed to investigate the establishment of a naval fleet Air Arm similar to the RN. The RN had six partially completed Majestics, and the RAN decided to purchase two of them, along with two Carrier Air Groups and establish a naval air station.

The two Majestic Class HM ships, Terrible and Majestic, were purchased and renamed Sydney (III) and Melbourne (II). The advent of jet-propulsion aircraft drove post-war technological developments. It led to a rapid development in the designs of carriers to accommodate more dynamic jet aircraft.

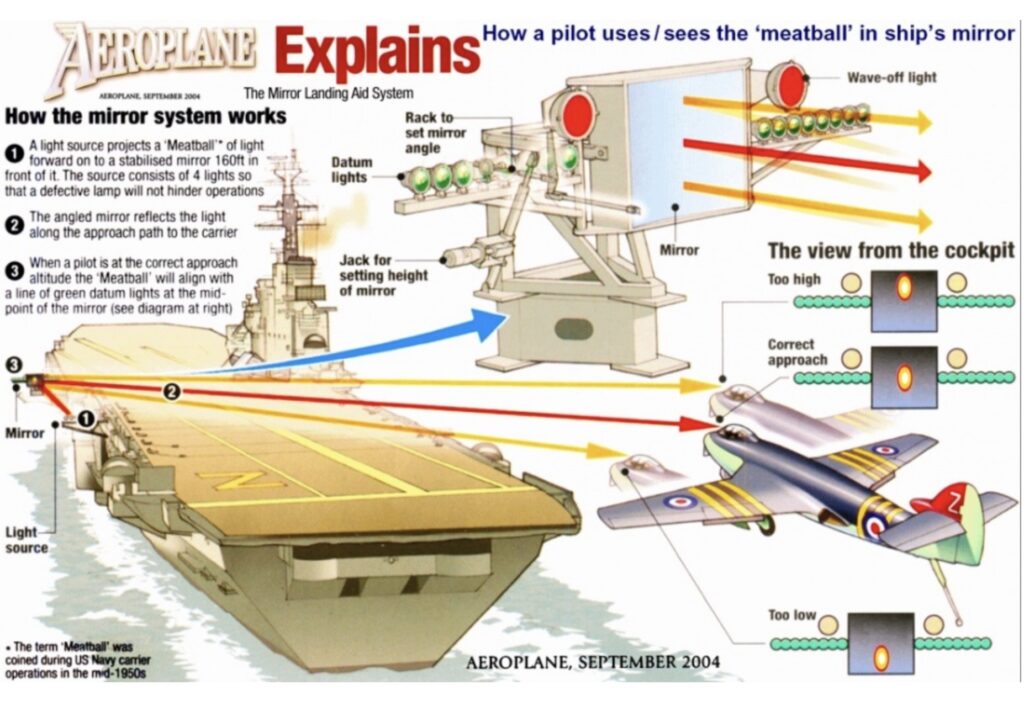

Work resumed on Melbourne in 1949, where the RAN decided to increase the flight deck lift size to accommodate larger aircraft coming into service. While the construction of the RAN’s first carrier, HMAS Sydney (III), was too advanced to include these modifications, the construction of Melbourne was still at an early enough stage for their inclusion. In 1952, RAN added a modified flight deck of 51/2 degrees, a steam catapult and a mirror deck-landing system.

On 28 October 1955, the ship was officially named and commissioned into the RAN as HMAS Melbourne under the command of Captain Galfrey Gatacre. The first aircraft to land on her was a Westland Whirlwind helicopter from the RN. Not long afterwards, the first fixed-wing landed was a Hawker De Havilland Sea Venom and then a Fairy Gannet during trials in the English Channel.

Her voyage to Australia was via the Mediterranean Sea, through the Suez Canal, before crossing the Indian Ocean and arriving in Fremantle on 23 April 1956. The RAN revealed in media interviews that Melbourne could deploy her jet aircraft by night and day. It gave Australia a naval advantage not possessed by any land-based air force operating jet aircraft in the region.

The Melbourne’s base was at Jervis Bay, where 64 aircraft that the Melbourne had brought from the UK were transferred ashore in July 1956. Melbourne maintained a regular program of exercises, training and maintenance over the next decade, including annual deployments to the Asia-Pacific region.

Melbourne sailed to Hervey Bay the following month to provide flying training for the aircraft squadron. Unfortunately, Lieutenants Barry Thompson and Keith Potts of 808 Squadron were both killed when their Sea Venom crashed into the sea shortly after take-off. The cause of the accident was never determined, although investigators believed insufficient wind speed over the deck was the main reason.

Immediately after her arrival, she sailed for Port Melbourne in late November to participate in the staging of the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games. The Flagship band was part of the RAN massed bands that gave a polished display in the main stadium. One formation display was the presentation of simultaneous marching and playing into a design of the five interlocking rings of the Olympic symbol as a prelude to the official opening ceremony.

Personnel from Melbourne also acted as marshals at various venues every day of the event.

Another notable highlight was returning to Melbourne at the end of January 1959 to take part in filming scenes for the movie On the Beach, directed by Stanley Kramer. Melbourne was also the abandoned hulk in the adaption of Neville Shute’s post-nuclear holocaust novel of the same name.

HMAS Voyager

Advances in destroyer design in the UK during the mid to late 1940s led to the design of the Daring Class ship, described initially as a light cruiser. They departed from the conventional destroyer in design, armament and number of personnel carried. While still retaining the strike power of a light Cruiser, it possessed the latest anti-submarine detection devices.

The Australian-built Daring Class destroyers were like others built for the RN. Still, they had modifications to suit Australian conditions such as excellent ventilation and air conditioning, cafeteria messing and bunks instead of hammocks.

Initially, the government ordered the construction of four Darings for the RAN, but only three – Voyager (II), Vendetta (II) and Vampire (II) – were eventually built. Voyager was ordered in December 1946 from Cockatoo Island Dockyard and became ship number 188.

HMAS Voyager (II) was part of the first prefabricated, all-welded ship built in Australia. At the time, the Darings were the RAN’s largest conventional destroyers. Voyager was launched on 1 March 1952 by Mrs (later Dame) Patti Menzies, wife of the Prime Minister.

They were designed and built as versatile, multi-purpose “Gun Ships” with three separate weapon control systems to control the primary and secondary armament.

Voyager spent most of its time stationed in South-East Asia, returning to Australia for major maintenance and upgrades. In January 1963, Captain Duncan Stevens assumed command of Voyager from Commander Willis. The ship spent most of the year in Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo. Voyager arrived at the Williamstown Dockyard in Melbourne in August of that year for a major refit.

She replaced Voyager I which lay helpless aground at Betano Bay, Timor in September 1942 after she arrived, landing troops to supplement the Number 2 Independent Company attached to Sparrow Force of the 8thAustralian Division who would not surrender after the Japanese occupation. A regular Japanese reconnaissance plane sighted the stricken ship. It went back to its base at the capital of the slender island. Then came the bombers and in anticipation of the bombing raid, it was decided to abandon ship. A Japanese bomb collected Voyager’s stores including crates of beer. The Voyager crew set of demolition charges which destroyed the ship. The Japanese troops followed the bombing. Luckily, HMA ships Kalgoorlie and Warnambool managed to safely evacuate the Australians.

The training exercise

Voyager emerged from the dockyards in late January 1964 with a significant percentage of her crew new to the ship. She sailed to Sydney in preparation for another deployment to South East Asia. But before doing so, she diverted to Jervis Bay on Thursday, 6 February 1964, to participate in training exercises with HMAS Melbourne. Both ships anchored in time for the crews to enjoy a weekend of sport and recreation. However, when Voyager was taking station on Melbourne for entry into Jervis Bay, she made a mess of manoeuvring into position. She had to turn astern to avoid impact with the bigger ship.

On Monday, 10 February, they sailed from Jervis Bay before dawn to conduct a series of trials and exercises.

The two ships used the opportunity to correct problems found in the dockyards and refresh everyone on sea-going routines. For Voyager, this included a shore bombardment and anti-submarine exercises with the British submarine Tabard, all while circling Melbourne. Melbourne practised anti-aircraft tracking, conducted radio sea trials, and exercised emergency stations.

At 18:00, Voyager had closed in on Melbourne for the first time that day to transfer mail by heaving line. After the transfer, Voyager was stationed five miles ahead of the carrier for over an hour as they waited for darkness and orders to take up station from the senior ship. During that time, they conducted radar calibration trials. The sun set at 19:45, and Voyager was ordered to rejoin Melbourne in preparation for the night flying exercises. It was a moonless night; the weather was fine, and the sea was calm on a slight swell.

That night, Melbourne was involved in night flying exercises that involved high-tempo night landing evolutions with Gannets and Sea Venoms out of the NAS Nowra base. Voyager’s role was that of planeguard, involving the rescue, if necessary, of aircraft personnel from the sea. The Gannets were due between 20:00 and 20:30, and two Sea Venoms between 20:30 and 21:00.

It was the first time both ships were involved in close quarters in the six months since their refit. Both ships were “darkened” during the exercise, with only navigational and operational lighting in use.

Melbourne’s Commanding Officer, Captain John Robertson, signalled to Voyager that the course the carrier would proceed while operating the aircraft was 180 degrees at 20 knots. The fundamental principle during this exercise is that the destroyer keeps clear of the carrier while she operates the aircraft. The position Voyager was to take is called “Planeguard Station No 1” – a position 20 degrees on the carrier’s port quarter at a distance between 1,500 and 2,000 yards.

With both ships heading north and the flying course to the south, Voyager was in a position when Robertson gave the signal for both ships to turn together 180 degrees. This movement happened at 19:50. However, the winds were light and variable, and Robertson had to alter speed and course to get the maximum headwind across the flight deck. He signalled minor variations in the course to Voyager. By the time the Sea Venoms were due to arrive, they were on a course of 175 degrees and at a speed of 22 knots. When the Sea Venoms arrived for their “touch and go” exercises at 20:30, Robertson again altered course to 190 degrees. Throughout these simple manoeuvres, Voyager maintained her correct station.

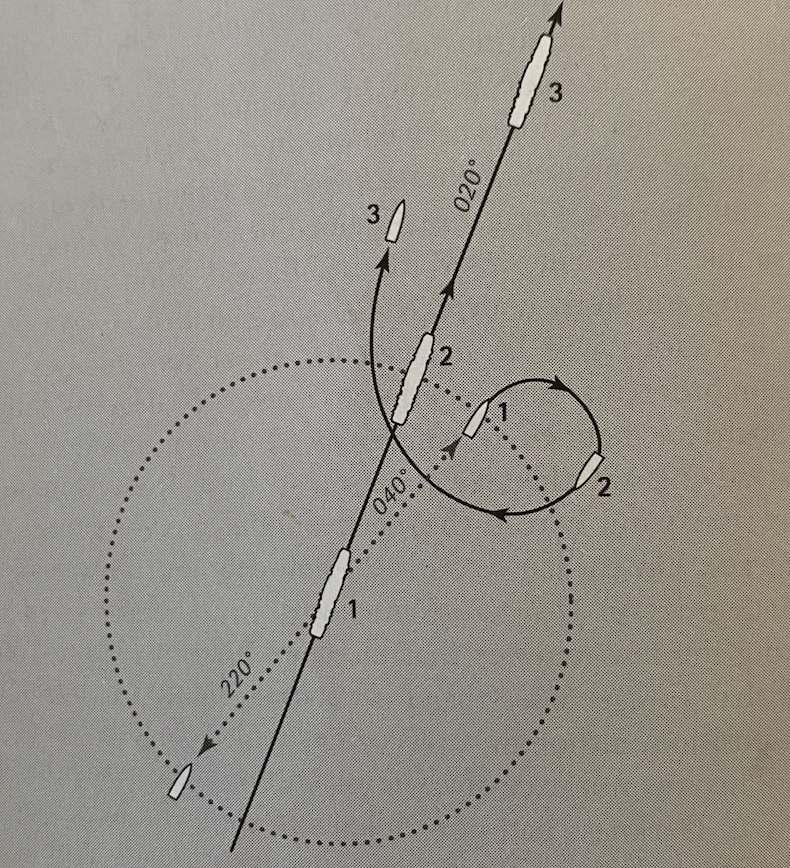

With insufficient wind available for the flying exercise on a southerly course, Robertson signalled Voyager he would delay operations for about ten minutes. At 20:41, Robertson ordered a turn starboard together to 020 degrees. This manoeuvre placed the Voyager ahead of the carrier.

After steadying on a new course, Robertson decided to compare the wind across the deck on a more easterly course of 060 degrees, and they changed at 20:47. Voyager was “ahead” of station to starboard of her correct position 30 degrees on Melbourne’s port bow, but still 2,000 yards away.

The fatal manoeuvre and rescue

After deciding the wind was better on the previous course, at 20:52, Robertson signalled a turn back to 020 at 22 knots, with ships turning together to port. While they were still turning, Robertson signalled, “flying course 020 speed 22 knots”. For Voyager, sailing just ahead of and on the starboard (right) side of the carrier meant repositioning to port and astern. The safest and most logical method to do this would involve a turn to starboard, allowing Melbourne to pass, and conducting a long progressive arc around the back of the carrier to take up Planeguard Station No 1.

Voyager immediately turned starboard to loop around and behind Melbourne. However, for reasons unexplained to this day, the unthinkable happened. The destroyer inexplicably reversed its course.

Maybe it was confused and disorientated in the darkness, but Voyager turned to port. Melbourne didn’t raise any alarms immediately as the bridge crew on Melbourne thought it would carry out a fishtail or zigzag course to slow its momentum. Manoeuvring ships at sea requires a high level of skill and concentration.

According to a junior member and one of only two survivors on Voyager’s bridge, while this was happening, Stevens was conferring with his navigator and Communications Yeoman, most likely over Melbourne’s signals. It did not occur to Robertson that the Voyager was unaware of her position relative to Melbourne, so no one sent urgent messages or signals to warn Voyager.

Failure to do so would plague and haunt Robertson during the inquiries and make him the Navy’s scapegoat. The first inquiry determined that he could have prevented the collision, considering this was only two minutes before the accident. The colossal carrier could not slow or change course to avoid a collision. Weighing 20,000 tons, it cannot turn like a speed boat.

When officers on the carrier realised Voyager was still turning to port and 800 yards away, they knew it would pass in front of them, and it was too late to avoid a collision.

Between 20:55 and 20:56, Robertson ordered Melbourne “full astern both engines”, and Captain Stevens ordered Voyager “full ahead both engines. Hard a-starboard” in a futile attempt to avoid a collision. He hoped that by doing this, Voyager would either pass ahead of Melbourne or turn inside her path. Not so. They were only 300 yards apart.

After giving his last order to try and change the destroyer’s course, Stevens told his Quartermaster they were in an emergency and to “pipe collision stations”. At 8:56 pm, the carrier hit Voyager just aft of the bridge, killing the senior officers on the bridge on impact. Keeled over, Voyager was pushed laterally for a few seconds before the immense forces sliced her in two.

There were men in the forward cafeteria of the bow. After separating from the rest of the destroyer, the bow heeled sharply about 60 degrees onto its starboard side and turned upside down. The men tried to exit through the escape hatches as water poured in, but some wouldn’t open. Nor were lifejackets readily available. About 128 men escaped through the hatches out of the ship’s company of 314. They tried to stay afloat in the oil-covered water, making it difficult to see and breathe. Ten minutes later, the bow sank, taking trapped men with it.

Captain Robertson ordered boats in the water and nets over the carrier’s side for survivors to clamber up. They also deployed eight helicopters to search for survivors in the water. Another six ships arrived to help in the search and rescue – HMAS Stuart and minesweepers Hawk, Gull, Ibis, Curlew and Snipe. It was a scene of panic and turmoil at night.

The other half of Voyager defiantly stayed afloat after the salvage and rescue operations began. However, after 30 minutes, the bulkhead forward of the boiler room collapsed, and the stern started to rise out of the water. The injured were lowered into life rafts, while others jumped into the sea after somebody gave the order to abandon the ship. The Voyager sank to lie some 150 metres deep, 20 nautical miles from Cape Perpendicular.

A Navy Wessex helicopter arrived to lift men out of the water. But it proved limited in its ability to assist mainly because the downdraught from its blades was a full gale force and made the ocean surface too rough, blinding those in the water with oily sea spray. Also, hardly any of the sailors had any wet winch training. Consequently, the helicopter rescued very few men.

Over the next three hours, Melbourne’s ship’s company desperately tried to recover those in the water. The ships managed to rescue 232 men. On survivor, told of 56-pound shells exploding in the magazine below the water level as Voyager started to sink. “I was terrified. I didn’t know whether I was going to be blown up or drowned”.

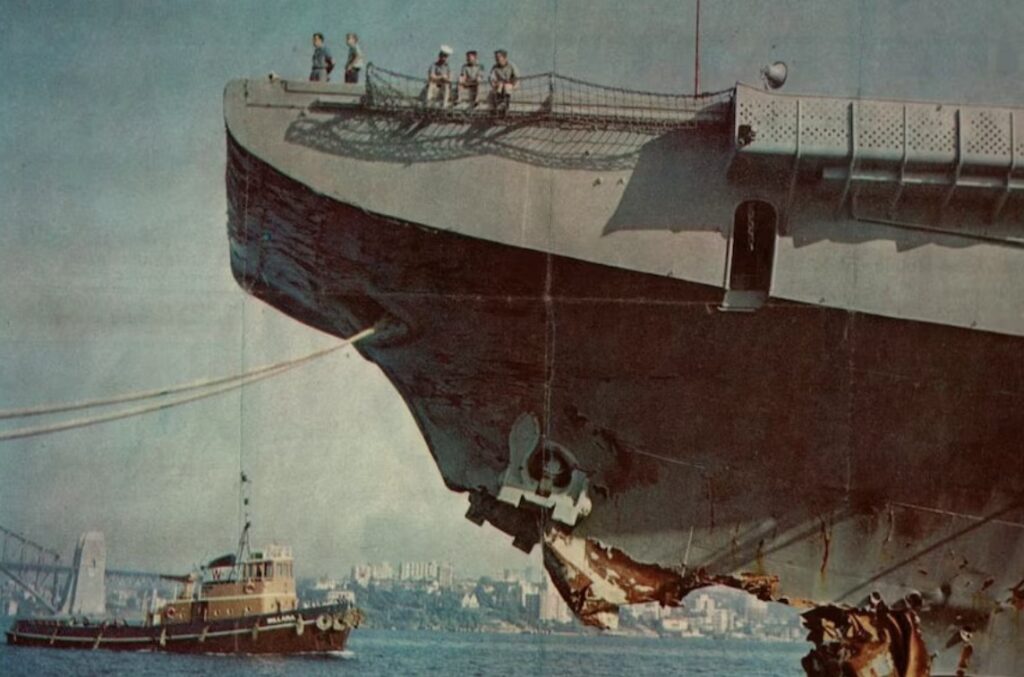

On the following Wednesday morning, a lonely, gouged and torpid warship – an aircraft carrier no less and once the pride of the fleet – limped into dry dock at Garden Island in Sydney with a massive gauge out of its bow.

The inquiries

The nation was shocked as images of the damaged bow of Melbourne and the rescued men came to light. For RAN, the accident immediately put the spotlight on the naval hierarchy. The Voyager tragedy came just three months after senior officers sent five junior officers in a whaler from HMAS Sydney to sail around Hook and Hayman Islands in the Whitsundays on an out-of-sight sailing exercise in dubious weather. Rescuers found two dead inside the upturned whaler, but they never located the other three men. They were presumed drowned. Sadly, four midshipmen who served on Sydney during this tragedy were among those lost on the Voyager. There were six other major incidents involving RAN ships in the preceding four years.

Captain Bill Dovers (later Rear Admiral) was initially convicted “of failing to keep himself informed of the progress of the whaler” at a court martial. However, the Naval Board overturned this, effectively sending the captain on a promotion course. The public saw this as RAN not keeping its officers accountable, which led to Parliament and the public lacking trust. Many saw RAN as an old boy’s club protecting each other.

It didn’t help that the Naval Board were not forthcoming with details about the Voyager accident during the night of the collision with the press or its political masters. The reason for this was partly a reflection of the confusion at the time. It took Robertson sometime after the accident in total darkness to fully understand the gravity of the damage and eventual fate Voyager suffered and report that back to his superiors. Based on his early reports, RAN headquarters initially thought Voyager had lost her bows, which normally would not lead to a significant loss of life.

Uncomfortable rumours circulated after the incident. How could the RAN allow such a tragedy where one ship sliced another in half on a training exercise during peace time? These deaths were not a sacrifice for the country’s defence but resulted from officer error or, quite possibly, negligence.

Thus, it was no surprise that the Naval Board’s immediate action was to set up its inquiry into the tragedy because this is what always happened. They believed a routine Naval Board inquiry was the most effective means of determining what happened.

However, Prime Minister Menzies had other ideas. He feared the Navy would close ranks and attempt a cover up. Peers investigating their members didn’t sit well with him, particularly after the Whitsunday Whaler fiasco. Given the magnitude of the disaster, he wanted a Naval Court presided over by a judge. He made a public announcement saying an inquiry would immediately begin. But he didn’t know about the many bureaucratic and legislative hurdles that prevented him from getting his way without recalling Parliament to pass a law, which would delay any inquiry too long. Menzies also found out that a Marine Court of Inquiry under the Navigation Act 1912 excluded naval ships, and the Royal Commission Act 1902 also needed amendment to allow him to run his sort of inquiry.

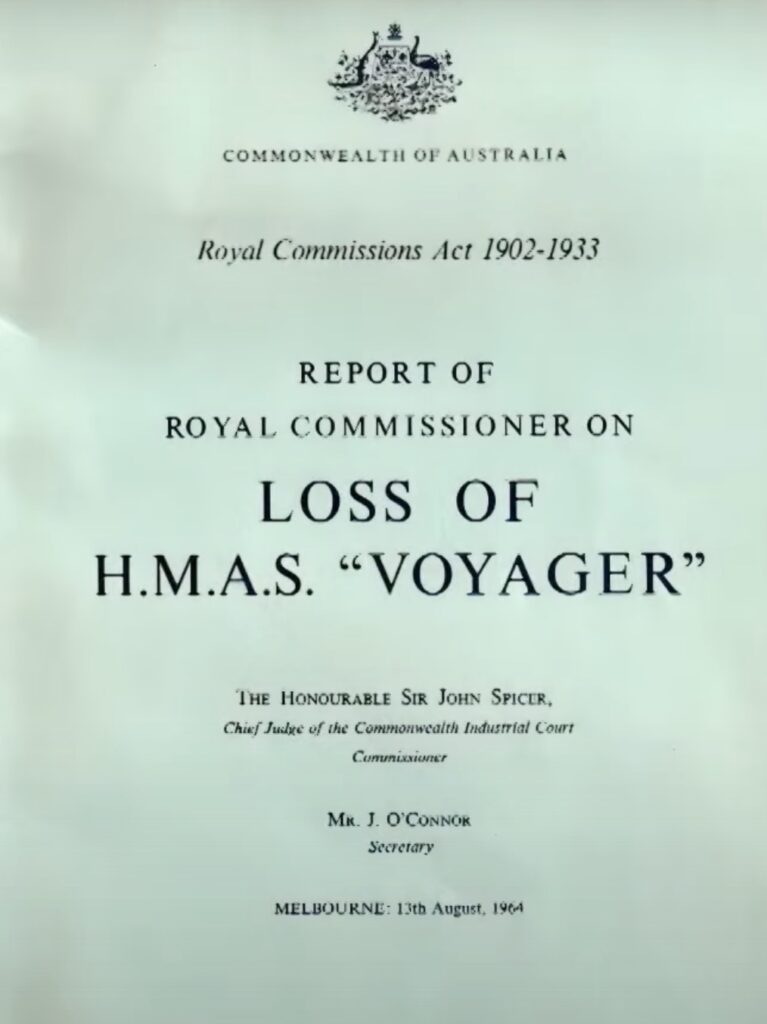

Still, Menzies hastily convened the first inquiry to try and lay the matter to rest quickly. He announced to the media on 13 February a Royal Commission to investigate the tragedy. It was clear from its terms of reference that there was little consultation with RAN. Because there was no provision under the act to appoint naval assessors, they could only be involved on an informal and advisory basis. As maritime historian Tom Frame wrote in his book The Cruel Legacy, it was perhaps Australia’s only unintentional Royal Commission.

Senior RAN officers felt the Navy’s honour was being attacked because the government, on behalf of the public, could not trust it to investigate its disaster. A retired naval commander wrote a scathing letter published in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“Naval incidents should be dealt with by Naval authorities and in this case the magnitude of the disaster in terms of loss of life or loss of ship should not be confused with the business of a straight-forward inquiry into a collision at sea. The tactical error which produced the collision remains the same error, whether Melbourne scraped paint from Voyager’s stern with no loss of life or sank her with all hands. With hysterical precision, the Government swept aside all the long standing and well tried naval procedures, implying immediately that its Naval Board of Admirals and its Flag Officer commanding the Fleet were incompetent to investigate the matter”.

Nevertheless, Richard Peek, Melbourne’s previous captain and Philip Stevens, captain of Voyager’s sister ship (until 14 February 1964), HMAS Vendetta, were appointed by the Naval Board to assist the Royal Commission Counsel. The government appointed Sir John Spicer, Chief Justice of the Commonwealth Industrial Court, as the Commissioner.

Robertson represented himself at the inquiry. His recollections of what happened changed several times, and the Commission’s Counsel alleged that he was trying to provide an account that served his own interests.

The Commission concluded that whatever the initiating cause of the accident, most likely a misunderstanding of the signals Robertson sent and what he ordered Voyager to steer, it seemed incomprehensible that no one on duty on her bridge was not looking where the ship was headed during its turning manoeuvre. According to Tom Frame, Voyager was at fault for failing to maintain a proper lookout and keep out of Melbourne’s way. The Commissioners believed that while Melbourne did what was required of her in terms of manoeuvring rules, her bridge staff were guilty of avoiding the development of a dangerous navigational situation and, ultimately, the collision. However, they emphasised the possibility that Voyager was on a steady course after the last turning circle. They saw Robertson’s failure to act decisively at this time as a contributing factor to the collision. In the end, though, based on legal advice, the Naval Board took no action against Melbourne’s officers.

During the Royal Commission, Robertson was temporarily relieved of command of Melbourne while she was on deployment in South East Asia after being repaired. Following the Royal Commission, the Naval Board decided they could not reappoint Robertson as commander, mainly as there was a likelihood Australia may get involved in a war with Indonesia, which would require substantial naval resources. Instead, Robertson was appointed as commander of the training facility HMAS Watson. He saw a land posting as a demotion and decided to resign. The media supported Robertson’s position and believed he was the scapegoat to protect the Navy and its most senior officers. The Daily Mirror’s editorial on 18 September said:

“His axing, thinly disguised as a shore posting, is a disgraceful under-handed move by the government”.

Parliament hotly debated Robertson’s resignation and request for a pension, dominating the news for over two weeks. But more was to come the following month, when retired Lieutenant Commander Peter Cabban, who was Voyager’s executive officer until four weeks before the collision, told Robertson, “Stevens frequently drank to excess while in harbour”. Although he never drank at sea, Cabban claimed “on several occasions”, the effects of alcohol prevented Stevens from exercising command when Voyager returned to sea. This revelation, in concert with a book written in collaboration with Robertson by a sympathetic retired RN Vice Admiral, Harold Hickling, and the persistent representations made by Victorian Liberal backbencher John Jess, were the catalysts for a new inquiry.

On 18 May 1967, new prime minister Harold Holt announced a further inquiry into the Voyager sinking in the form of another Royal Commission. Never before had the country seen a matter become the subject of two Royal Commissions. However, strictly speaking, the terms of reference for the second inquiry meant it was not a “second Voyager inquiry”. It did not allow the re-hearing of any evidence relating to events immediately before the collision. It was more an examination of Steven’s fitness to command, whether the Naval Board was aware of his lack of fitness, and if that was determined, whether they needed to alter the findings of the first Commission.

The second inquiry found that Duncan Stevens, the captain of Voyager, was medically unfit for command. It also absolved Melbourne’s captain and crew from blame. The credible argument was Robertson’s counsel convincing the three Commissioners, through detailed evidence, that the conclusion drawn in the first Royal Commission about navigation and time sequences before the collision was incorrect. He was able to demonstrate, with the help of Robertson’s experience, that the Voyager had not steadied on a course for a minute before the collision but was still turning. Also, the actions required by a turning signal meant Voyager had no discretion in manoeuvring, whereas in a flying signal, Voyager had complete discretion. Thus, Robertson was not obliged to challenge her movements and the original finding against him was overturned.

It was incredible that two Royal Commissions into the accident were inconclusive about the cause of the tragedy. The inquiries were criticised for poor investigations into the accident, although my readings of summaries of the inquiries showed they were pretty detailed and exhaustive. The difficulty was that the key witnesses – the officers controlling Voyager who made the decisions they did – died and went down with the ship, rendering meaningful conclusions almost impossible.

The aftermath

For many years after the tragedy, the fault was blamed on Melbourne, which only added to the survivor guilt felt by the sailors. Some couldn’t understand why Melbourne didn’t turn to avoid the collision. The helm position is below the flight deck, near the catapult launch control, and the helmsman cannot see out. Also, he cannot change course without orders. It’s a demanding watch. A ship the size of Melbourne cannot easily manoeuvre like a recreational speed boat. It takes up to one and a half nautical miles to bring a 20,000-ton ship to a halt. The only way Melbourne could avoid a collision was to turn away, hoping they had time.

The Melbourne-Voyager collision stunned the nation. It was a traumatic night for all those involved. Given those times, the media believed the RAN offered very little support to their sailors. Sailors were given a week’s survivor’s leave and then sent back on detail on sister ships. Allegedly they were ordered not to speak to the media, but I have seen press clippings less than a week after the accident interviewing survivors. Also, allegedly, there was minimal post-collision mental care or recognition of trauma. However, according to Frame, the Navy made every effort to “extend a hand of friendship and compassion to those who served on Voyager.

RAN experienced dramatic falls in recruiting numbers for many years afterwards, demonstrating a lack of faith in its abilities. This is despite the government announcing record spending in late 1964 that targeted increased personnel strength. Recruitment numbers did not recover for several years. One government minister at the time believed the Naval Board had no idea how low their public image had fallen.

While RAN did all it could to persuade the government to “rebut publicly the false accusations that had been made” against the Navy, there was a concession on their part of their inadequacies in the actions they were forced to take to improve their fleet operations. Instructions for tactical manoeuvring and signalling were amended; the location and operation of the bridge and operations room loudspeakers were reviewed, together with the placement and briefing of bridge lookouts; introduction of new mechanisms to remove the use of wheel spanners to open hatches; changes in the use of life-saving and safety equipment; a review of training into greater familiarity of life rafts and helicopter winching; and a higher proficiency standard for swimming ability.

Many survivors suffered after the collision. The average age of the survivors was 25, and many were young, raw recruits serving at sea for the first time. So too, did the sailors on Melbourne. They carried a heavy burden and stigma being on Melbourne after having to perform rescue duties. There were massive ramifications for the sailors involved. The injuries they witnessed traumatised them, with many leaving active service not long after, or after their career, being diagnosed with PTSD. Sadly, most of the rescued sailors subsequently died of cancer, believed to be caused by ingesting oil after the collision.

All this only added to the anguish of the surviving sailors, as they wanted closure and peace. They felt the RAN was ashamed of the incident, which led to its servicemen, the government, and the public losing trust.

Only recently, John Werner spoke about the crash for the first time. He was an electrician on Melbourne and knew about a refit carried out shortly before the incident. When he was on duty on the night of the accident, he set up the floodlighting on the carrier’s deck and noticed the floodlights had red filters. Before, they were white. He thinks the officers in the bridge on Voyager mistook the red for the stern and thus kept course to cut across when, in fact, it was the bow that was lit up. Werner thinks that because at least one of the red floodlights was facing starboard, it overshone the green navigation light, misleading the officers on Voyager into thinking it was the port navigation light.

However, the royal commissions didn’t think the red floodlights were the cause of the collision. They were critical of Captain Stevenson, deeming him unfit to command due to medical reasons. The first Royal Commission contentiously held Melbourne’s command team partially responsible for failing to prevent the collision. It led to the resignation of Captain Robertson.

The subsequent Commission overturned that finding, driven by a parliamentary backbench that railed against the Naval Board, which they saw as protecting itself by sacrificing its members. Unfortunately, like the first Commission, it could not determine the cause of the tragedy. The investigations were drawn out for the sailors involved and their families. They were also controversial, inconclusive and a source of additional pain.

According to some, including Professor Tom Frame, who has written two books on the tragedy, RAN didn’t adequately explain to its sailors why they thought the accident occurred, which led to much speculation akin to Werner’s thoughts. Werner said the inquiry dismissed his evidence, adding to the perception of secrecy and “treating junior sailors as an expendable commodity”. The Commissions were characterised by a hostile approach to witnesses and highlighted the unsuitability of a Royal Commission to investigate, mainly when the civilian investigators lacked naval knowledge.

In his paper on the tragedy, Chris Oxenbould believed the main reason for the collision on Voyager was the lack of sufficient lookout personnel. Her most experienced watchkeeper was absent, the Officer of the Watch was inexperienced, and the key lookout was on his first sea voyage. Captain Stevens, aboard Voyager, was the only experienced officer on either bridge. Every other officer had been recently posted onto Melbourne or Voyager, and this was their first night at sea in company for five months.

On 21 February 1964, memorial services were held throughout Australia to pay respects to the men from the Voyager who lost their lives.

On the shores of Jervis Bay in the town of Huskisson, there is an HMAS Voyager (II) memorial park. There is also a memorial at Voyager Park in the Sydney suburb of East Hills. Voyager Point runs alongside the Georges River just across the road. HMAS Cerberus also has an HMAS Voyager (II) memorial featuring a bronze statue of a sailor on a stone cairn.

Tasmania’s Maritime Museum at Devonport also has a memorial commemorating HMAS Voyager (II). It reads:

“The naval destroyer HMAS Voyager (II) was lost on the night of 10 February 1964 in a collision with the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne (II). Nine Tasmanians were serving on the Voyager (II), four of whom were among the eighty-two men who died that night:

AB Neil Benjamin Brown

Ordinary SMN John David Clayton

Ordinary SMN Graham Dennis Fitzallen

Leonard Charles Lehman (cook)

Postscript

The repair work kept Melbourne in Sydney for three months. She returned to sea on 11 May 1964. She attended her annual South East Asian deployments, which included time in New Guinea, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia.

She participated in many overseas exercises, including FOTEX, WINCHESTER and FIRST TIME. During the latter exercise, a Gannet experienced a total loss of power on take-off and ditched into the sea, about 500 metres from the ship. Helicopters quickly recovered the crew.

Melbourne also spent time in American waters. In 1968, she underwent a major refit at Garden Island to accommodate new A4 Skyhawk aircraft and radar communication equipment.

In late May 1969, Melbourne returned to sea to participate in US Navy exercises. In the early hours of 31 May, in the South China Sea, Melbourne’s captain ordered USS Everett F Larson to take up a planeguard position astern of Melbourne from off her starboard bow. At one stage, Larson made an incorrect turn and was on a collision course with Melbourne. Corrective action from both ships avoided a collision. This event not only revived memories of the Voyager tragedy five years earlier but also pre-empted another tragedy to come.

In the early hours of 3 June, in a manoeuvre almost identical to the near miss with Larson a few days earlier, the destroyer USS Frank E Evans crossed Melbourne’s bows while attempting to move in the planeguard position and was cut in two. The forward section of Evans sank quickly while Melbourne’s crew secured her stern section to the starboard side. This action enabled rescuers to search that part of the ship for survivors. Seventy-four of Evans’ crew lost their lives, and Melbourne once again sustained extensive damage to her bow section. Search and rescue operations began immediately, saving 199 men. Melbourne steamed towards Singapore Harbour that afternoon with flags at half-mast.

A joint US Navy/RAN Board of Inquiry into the tragedy held Captain Stevenson partly responsible, stating that as Commanding Officer of Melbourne, he could have done more to prevent the collision from occurring. However, a subsequent RAN court martial cleared him of any responsibility. The integrity of the initial Board of Inquiry has since been questioned, notably as it was presided over by Rear Admiral Jerome H King, US Navy, the officer in overall tactical command of Evans at the time of the collision. The Captain of Evans, Commander Albert McLemore, was asleep in his bunk during the manoeuvre, leaving two very inexperienced watchkeeping officers on the bridge. All observers and those knowledgeable of naval procedures and operations knew the blame solely laid on the appalling incompetence of the US ship, even though the inquiry didn’t come to that conclusion. Stevenson’s defence council, Gordon Samuels, QC, later Governor of New South Wales, said that he had:

“…never seen a prosecution case so bereft of any possible proof of guilt”.

Melbourne continued its service in the RAN with deployments around the world. While there were other incidents, there were no more collisions with other ships.

She entered Sydney for another round of maintenance and refit in November 1981, and the following February, the federal government announced arrangements to purchase the British aircraft carrier HMS Invincible from the RN to replace the ageing Melbourne, which would be placed in “contingent reserve”.

She was decommissioned on 30 June 1982, having spent 62,036 hours at sea and travelled 868,893 nautical miles. It was a fittingly grey, cold and rainy day for her farewell from Sydney to the trouble-prone but immortalised (in film) HMAS Melbourne as she was towed out of the harbour for the last time bound for a Chinese scrap metal heap in April 1985, thus ending a tumultuous 26-year career as an aircraft carrier.

This blog is dedicated to the memory of Able Seaman Peter Robert Carr, who was onboard Voyager when it collided with Melbourne and sunk. He went missing and his body was never recovered. Carr is the uncle of a mate, Brad “Bluey” Carr, who also served in the Royal Australian Navy.

An excellent read for those not familiar with this major maritime incident.

I think that the reference to little post trauma care should be put in context of the time in occurred and noted in the article.

Perhaps a statement, consistent with practices within the RAN, those impacted were not provided with limited post trauma care.