“Unfortunately, conjecture based on limited facts has produced “research” trumpeting catastrophic fears of extinction”. Jim Steele

Introduction

“Our planet now faces a global extinction crisis never witnessed by humankind. Scientists predict that more than 1 million species are on track for extinction in the coming decades”.

As the world commemorates another Endangered Species Day, you will undoubtedly read or hear claims like the above. According to mainly non-government organisations, humans are causing a sixth mass extinction event, and the Earth is currently experiencing the most significant loss of life in recorded history. But it is not without hope because we must “restore and repair” our natural environments by “protecting” at least 30 per cent of our lands and oceans by 2030. And the urgency is no greater than in Australia because we have the world’s worst records for wildlife extinctions.

But you only have to study these claims closely to understand that there is very little evidence of rapid net loss of species, and a mass extinction event is merely speculation without substance.

Past extinction events

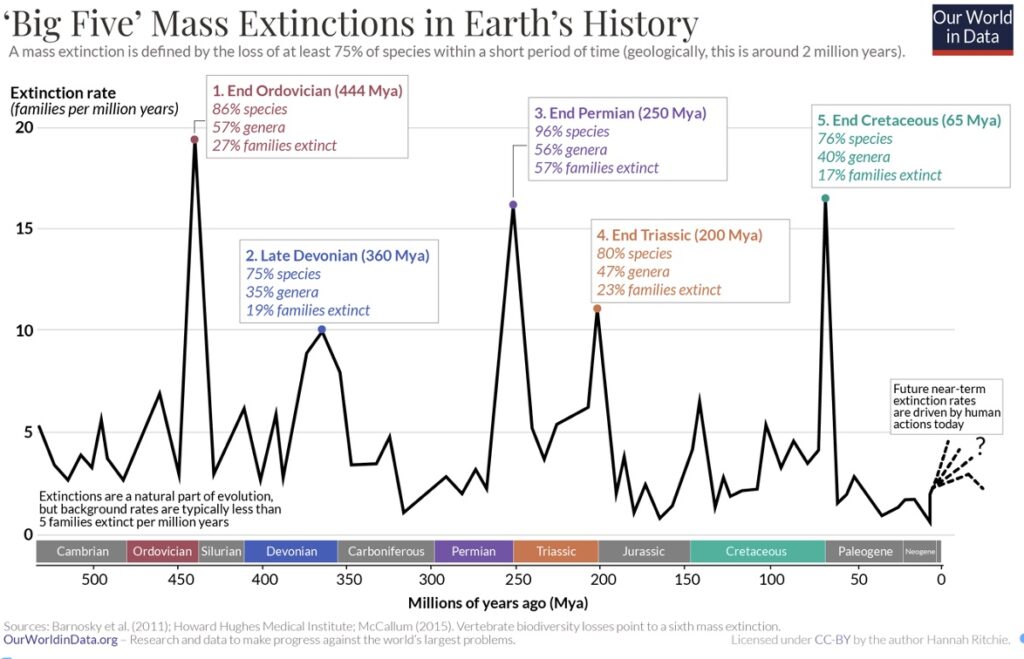

The science community defines a mass extinction as losing at least 75 per cent of species within a short period. Geologically speaking, this is around two million years. Extinctions are a natural part of evolution, but background rates are typically less than five Families going extinct every million years.

According to the evidence from fossil finds, there have been five previous mass extinction events.

The first was 440 million years ago, at the end of the Ordovician Period. Because animals hadn’t yet conquered land, the loss of life was confined to the sea. About 85 per cent of marine animals disappeared, including 27 per cent of Families. Many believe the primary cause was a significant ice age in the southern hemisphere.

The second mass extinction occurred 360 million years ago during the late Devonian Period. It comprises a series of events that again affected the marine communities. The primary reef builders were virtually wiped out. No single cause was to blame, but 70-80 per cent of all animal species, including 20 per cent of Families, were eliminated.

Towards the end of the Permian Period, something killed 90 per cent of the plant species in what is known as the third mass extinction event, about 250 million years ago. Less than five per cent of the sea animal species survived, with 57 per cent of Families wiped out.

The end-Triassic Period extinction event – the fourth mass extinction – occurred 252 to 201 million years ago. It resulted in the demise of about 76 per cent of all marine and terrestrial species, including 20 per cent of all taxonomic Families. Many believe this extinction allowed dinosaurs to become the dominant land animals.

The fifth mass extinction event is probably the most widely known. The end-Cretaceous Period saw the sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species about 66 million years ago. Infamously, it was the extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs.

Are we in the midst of a sixth massive extinction event caused by humans?

The idea that we are causing a mass extinction event with our profligate living standards was first raised in 1970 by the founder of Earth Day, Senator Gaylord Nelson, who quoted Dr S Dillon Ripley from the Smithsonian Institute:

“In 25 years, somewhere between 75 and 80 per cent of all the species of living animals would be extinct”.

Biologist Norman Myers followed in the same vein in his book The Sinking Ark: A New Look at the Problem of Disappearing Species, published in 1979. He predicted that a million species would become extinct between 1975 and 2000. Wilson calculated up to 30,000 yearly extinctions, or around three species per hour, just in the tropical rainforests.

Other prominent scientists and Al Gore have also made estimates of between 17,000 and 100,000 annual extinctions.

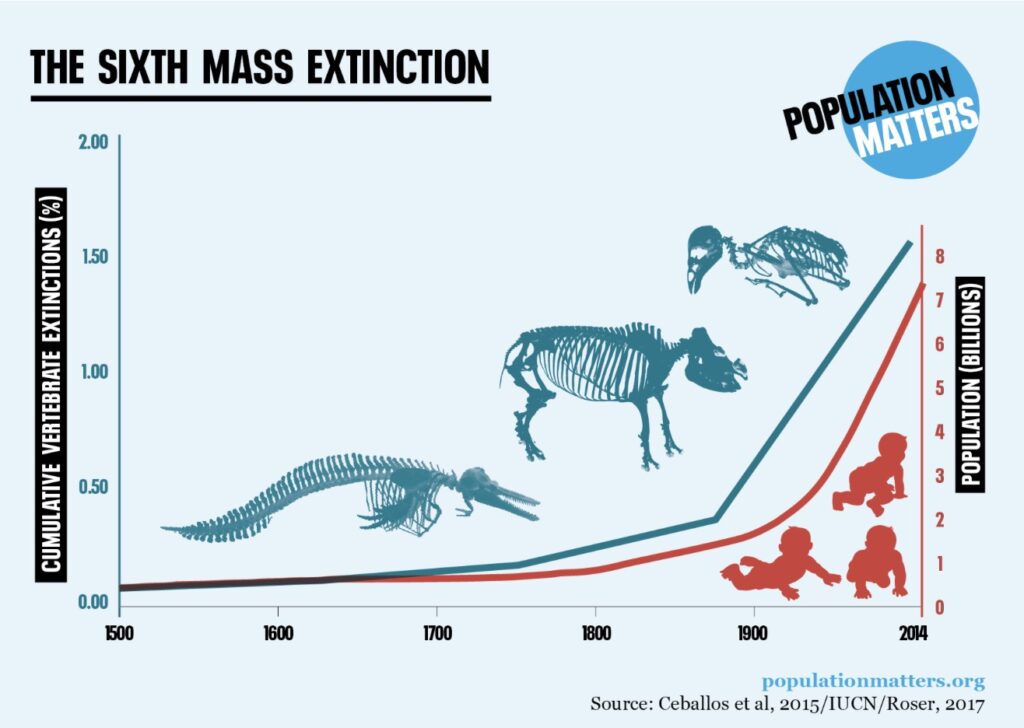

A study published in 2015, known widely after one of the co-authors as the Barnosky research, claims that the average rate of vertebrate species loss over the last century is 100 times higher than the background rate. Their research suggested that 617 vertebrate species have become extinct, or possibly extinct, since 1500. However, a 2011 paper revealed that only six continental birds and three continental mammals have gone extinct since 1500. Indeed, 95 per cent of bird and animal extinctions since 1500 have occurred only on islands. It suggests a particular case involving species with a much smaller geographic range and other factors that make them more prone to extinction.

The basis for making bold statements and assertions on past and future extinctions is the species-area relationship. It describes the relationship between the area of a habitat or part of a habitat and the number of species found within that area. If the area of a habitat, say a forest, reduces, so does the number of species in the forest.

The most famous estimate of species extinction rate using the species-area relationship came from biologist Edward O. Wilson in his 1992 book The Diversity of Life. He argued that because there was a one per cent area loss of forest habitat worldwide, using what he called “maximally optimistic” species-area calculations, “the number of species doomed [to extinction] each year is 27,000. Each day it is 74, and each hour 3”.

Losing 27,000 species per year since 1992 equals 810,000 species now extinct. Wilson said the rate of forest loss had been going on since 1980, meaning well over 1.1 million species lost forever in 43 years. There are many other estimates of species loss by varying orders of magnitude, including one as high as one species per minute (over half a million per year).

Marine biologist John Briggs wrote an article in 2016 about these estimates, saying that in the past 50 years, “a wave of propaganda” of exaggerated numbers and talk of an impending sixth mass extinction has washed over us, “making the public feel guilty”. Briggs was sceptical of the calculations on the background rate of extinction that prevailed several million years ago. His analysis has come to different conclusions, estimating 1.5 extinctions per year beyond what is considered normal. He argued the formation of new species balances this loss and concluded:

“Without evidence of a significant net loss of species, mass extinction is merely speculation without substance”.

It didn’t stop Paul Ehrlich from re-appearing in the media as recently as 1 January last year. CBS News 60 Minutes program completely ignored Ehrlich’s previous failed predictions about planetary doom. They allowed him to engage in more outrageous claims, predicting that we are on the cusp of a sixth mass extinction event, saying that the “next few decades will be the end of the kind of civilisation we’re used to”.

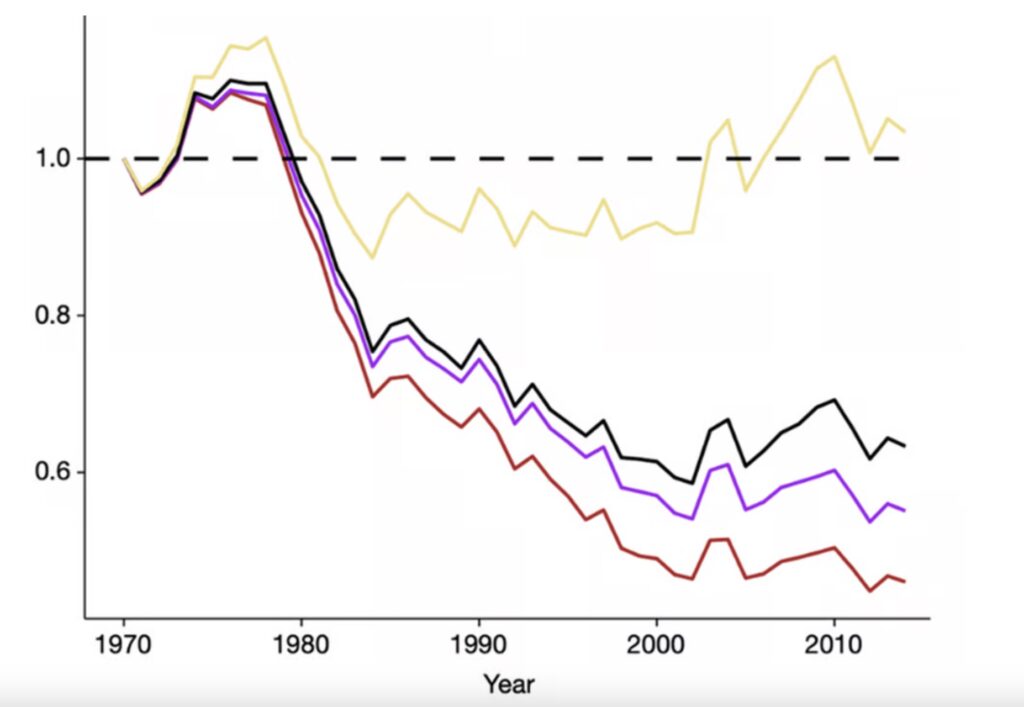

Surprisingly, or perhaps not, the repository for the extinction claims by media, government agencies and environmental organisations has come principally from a non-government “charity” organisation. Since 1978, the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) has produced a biennial assessment of the changing state of vertebrate animal populations called the Living Animal Report, which features its Living Planet Index (LPI). They tell us their analysis is scientifically robust.

The Index is based on the decline of some selected species, which is claimed to represent the decline of the species of the “living world”.

The 2018 report, released to coincide with the United Nations 15th Conference of the Parties (COP) summit in Montreal, declared that humanity had been on a rampage, wiping out 60 per cent of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles since 1970. Through extensive media coverage, the “world’s foremost experts” warned “that the annihilation of wildlife is now an emergency that threatens civilisation”.

However, two independent groups of scientists looked closely at how WWF calculated their LPI and refuted their work.

They concluded:

“If these extremely declining populations are excluded, the global trend switches to an increase”.

This critique didn’t change things for WWF’s following report, published in 2022. They doubled down on the use of extreme outliers. The other group of scientists examined the latest Living Animal Report published in 2022 and also found an over representation of extreme outliers.

The Finnish scientists even suggested the problem was worse than first thought because the LPI ignores abundance and only measures proportional declines or increases. They found the more populations of species vary in their rate of increase or decrease, “the more downwardly biased the LPI will be as a measure of abundance”. Even worse, their future calculations showed a downward past bias:

“…since previous index values are multiplied with the current one [and as a result] the trouble with the LPI methodology is deeper…and cannot be resolved by removing extreme population trends from the analysis”.

In essence, the claim that the LPI shows a decline of more than 50 per cent of vertebrate species since 1970 is driven by less than three per cent of vertebrate populations. There are no global trends across typical vertebrate populations. A study using the world’s largest database of long-term species abundances found:

“Most populations (85 per cent) did not show significant trends in abundance, and those that did were balanced between winners (eight per cent) and losers (seven per cent).

Australian scientist Grahame Webb believes certain scientists have overstated the risks of wildlife becoming extinct by using deliberate and gross exaggerations. He believed those designating species as endangered or threatened are beneficiaries of funding that flows due to these listings. Thus, he says, “the potential for self-serving assessments has long been recognised”.

One example the South East Forest Association (SETA) brought to my attention is a WFF-led study that alleged that the logging of native forests in south-east New South Wales “locked in” species extinction. The authors even issued a media release before their research paper was peer-reviewed and published. Preservation scientist Professor James Watson, a former employee of the Wilderness Society, said, “many species that depended on forests were now being sucked into “an extinction vortex” because of logging”.

The study’s authors claimed their research found:

“Long-footed potoroos (endangered), long-nosed potoroos (vulnerable) and southern brown bandicoots (endangered) had the highest proportion of the areas where they live affected by logging.”

The only problem not highlighted in the study is that most, if not all, of the long-footed potoroo’s habitat in New South Wales is in the South East Forest National Park where no logging occurs. In 2016-17, the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service invested over 25,000 camera days and nights across the range of the potoroo’s habitat in the national park. No camera photographed a single potoroo.

On the other hand, SETA shared a video from a camera set up in logged, thinned and prescribed burnt state forest in nearby Victoria for less than 100 days, and it captured footage of a long-footed potoroo.

As I have outlined previously, populations of southern brown bandicoots have declined in forests transferred to national parks. However, their numbers have increased in nearby state forests that are still subject to logging. A Threatened Species Scientific Committee Report of May 2016 showed the status of the bandicoots. The report assessed all the available quantitative estimates for population trends, which showed a 50 per cent reduction in bandicoot numbers in parks and reserves in New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia over ten years.

Long-nosed potoroos and bandicoots also flourish in actively managed state forests near Eden. Authorities have had to relocate them to populate Booderee National Park, which has failed to protect those species in the past.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is the principal scientific body that tracks species in its Red List. The Committee on Recently Extinct Organisms at the American Museum of Natural History maintains another list. Both are very similar. The Red List says just six per cent of species are critically endangered, nine per cent are endangered, and 12 per cent are vulnerable. They estimate that just 0.8 per cent of the 112,432 plant, animal and insect species in their data set have gone extinct since 1500.

That is nothing near the level of 75-90 per cent of all species on Earth to claim humans are causing the sixth massive extinction event. According to IUCN data, only one animal has gone extinct since 2000. It was a mollusc.

Using sensationalism and other methods to prove there is an extinction crisis

Not content with gathering data in the real world where the facts get in the way of trying to show a mass extinction event is happening, scientists have created their own data. In December last year, we learned that computer models predicted a third of vertebrates would die by 2100.

The only problem with the study by Giovanni Strona and Corey Bradshaw was that they admitted they didn’t have any reliable data, so they created a “synthetic Earth complete with virtual species and more than 15,000 food webs to predict interconnected fate of species”. They ran their model on Europe’s most powerful supercomputer and simulated results as though nothing was problematic. Unfortunately, it is common to make data up to fit a parameterised probability model. In statistical circles, this is called bootstrapping.

However, a computer food web experiment can hardly draw accurate world conclusions. In the real world, new connections always appear in the food web. No food resource remains underutilised for long. Any breaks in the food chain caused by a changing climate, disease, etc., are rapidly filled.

After publishing their work, Strona and Bradshaw wrote a media release breathlessly announcing their predictions and the media, like ABC, reported their work as factual.

In Australia, government departments and NGOs love to preface their stories, or appeal for funding, with the statement, “Australia has the highest mammal extinction rate in the world”.

For example, a LinkedIn post by the South Australian Department of Environment and Water claimed that “1,100 South Australian native plant and animal species are under the threat of extinction”. They blamed the usual suspects – habitat loss, land-use practices, pollution, invasive species and climate change. They then quoted South Australia’s 2024 Australian of the Year, environmental scientist Tim Jarvis AM, “which makes it our moral responsibility to do everything we can to halt that trend and protect and conserve our precious ecosystems”.

And, of course, the South Australian government is doing everything it can by introducing the state’s first Biodiversity Act to ensure its biodiversity is “better protected”. It is a pity they don’t hold themselves accountable and report in the future how well they are doing instead of blaming everything and everyone else when their actions don’t work.

To say they have 1,100 species under threat of extinction is a very loose statement without any evidence or causal links. Many species are listed as threatened simply because they have a limited distribution or naturally low population numbers. That doesn’t mean they are in danger of extinction, and I certainly wouldn’t trust a bureaucrat in a city office to oversee saving them anyway.

A study published in 2019 claimed that insects are heading for global extinction in a few decades. And because of their importance to agriculture, this will result in the collapse of food production. The only problem is the work of Francisco Sanchez-Bayo and Kris Wyckhuys is full of bugs.

They only found declines in insect numbers because they only looked at studies that showed declines. That may make sense if they were looking for the causes of particular insect species and population declines, but as an attempt to quantify the rate of decline, their work is flawed.

For example, while 260 British moth species declined, 160 increased significantly, but the study only included the declining species. Also, when a species moves into a niche or habitat abandoned by another species, the study only counted the abandoned species. Furthermore, it isn’t a global study because there are no records of wild insect numbers in India, China, the Middle East, Siberia and Australia. This study documents a severe decline in specific insect populations in Europe and the USA, which is not unexpected because these areas universally use modern agricultural techniques. It highlights we need higher-yielding technology to produce more from a smaller area and reduce the use of insecticides.

Despite past global warm periods bursting with abundance and life and human civilisations prospering, computer models tell us any warming we face now means we will all die. According to a Research Fellow at the University College London, Alex Pigot, the world has warmed by roughly 1.2OC since the pre-industrial period (or what he should say – since the end of the Little Ice Age) and “many species are already exposed to increasingly intolerable conditions, driving some populations to die off”.

It is a pity the media release doesn’t mention the qualifications of Pigot’s work. Still, Pigot and his co-authors admit their study didn’t consider several essential factors, and their modelling overestimates the risks. They failed to consider migration because they believed global warming was happening too fast. They assume there are abrupt pulses of global warming and admit shortcomings in considering short-term responses to these assumed pulses.

However, the biggest problem with their claims that species are at risk from abrupt climate change is that such a change has occurred in the past, and species were just fine. The Younger Dryas was a severe and abrupt cooling event that occurred 12,900 years ago and lasted about 1,200 years. The collapse of Lake Agassiz is considered the main trigger. This giant glacial lake once covered most of the North American continent, although the exact cause or causes are still hotly debated.

The abruptness and severity cannot be overstated, and the full impact was possibly experienced in as little as a couple of months. Yet the Younger Dryas is not described as an extinction event. Animals and plants adapted just fine to the abrupt change in temperature. It just shifted some balances, allowing some plants that grew in the background to dominate and flourish over other plants that preferred a warmer climate.

Debates about any recent mild warming often overlook that were it not for mammals’ rapid expansion and evolution during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, humans would probably never have come to be. Even David Attenborough has admitted that the tropics comprise about one per cent of Earth’s land surface but have 50 per cent of the known species. The danger of warming is clearly overstated.

The evidence shows it takes a lot more than a few degrees of abrupt temperature change to set off a mass extinction event.

Why don’t we hear about the species returning?

Around the world, there is an increasing number of species thought to be extinct that have been rediscovered. The following animals and plants are some examples.

In Australia, John Gilbert discovered Gilbert’s potoroo in 1840 near Albany. The last specimen was recorded in 1869, and it was so rare by the early 1900s that scientists thought it had gone extinct. Two people were trapping quokkas to study genetic variations at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in Western Australia. They rediscovered the potoroo after a chance encounter in 1994. However, extensive surveys of likely sites along the south coast failed to find more colonies. The tiny surviving population is now 30-40 animals strong and has been the focus of intensive recovery efforts.

While young individuals were born in the wild, none of these individuals were found as adults. It suggested most available home ranges in dense heath were already taken, and they could not establish new home ranges. The recovery plan focuses on shifting wild potoroos to new colonies on Bald Island. It is still scarce, but slowly, the population is building.

The pygmy bluetongue lizard was thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered in native grassland near Burra, South Australia, in 1992. It is currently known from 31 sites. The New Zealand southern right whale thought to be hunted to extinction in the late 1800s, has been rediscovered near the Auckland Islands. The forest owlet was rediscovered in India in 1997 by ornithologist Pamela Rasmussen after being unseen for 113 years. The largest squirrel in the world, the woolly flying squirrel, was rediscovered in Northern Pakistan in 1995 after it had been thought to be extinct. The Chinese crested tern is one of the rarest seabirds in the world. Only described in 1861, no confirmed sighting was made after 1937, and it was thought to be extinct. However, it was rediscovered on the Matsu Islands, and in 2004, another breeding colony was discovered on the Jiushan Islands. The discovery in Cambodia of a colony of giant turtles, once considered the exclusive property of the royal family and thought to be extinct, was made in a remote stretch of the Southern River. The Southern River terrapin, or ‘Royal Turtle’, had not been seen since the late 19th century. A species of pheasant long thought to be extinct has been rediscovered in Central Vietnam in 1996. The last known capture of the species was in 1928, but Edward’s pheasant was already rare five years earlier when a French ornithologist took 15 of the birds back to Paris. The Aleutian Canada goose was classified as endangered in 1967 when they numbered less than 500. They were so few that no one saw them for almost 25 years, and they were considered extinct. However, there are now more than 40,000 birds. The pale-headed brush-finch, previously thought extinct, was last recorded in 1969. However, four pairs of the bird were found in 1998 in the Rio Jubones drainage in southern Ecuador. It has now been downgraded from critically endangered to endangered.

A shrub collected by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Sydney has turned out to be a species not seen for 160 years and is thought by some to be extinct. Asterolasia buxifolia is so rare that it has no common name and has only ever been recorded at one location. Originally collected by early explorer and botanist Allan Cunningham in the Blue Mountains in the 1830s, the plant disappeared – so completely that it has not even been recognised in recent botanical books. It was rediscovered in 2000 in the Lithgow area. The beautiful orchid Cymbidium bicolor spp. pubescens was listed as extinct in the Red List. It was last collected in Sungei Buloh mangroves in 1891. Despite habitat loss, it has been rediscovered in 1996. Two researchers independently rediscovered a goldenrod species thought to be extinct in 1994. The Yadking River goldenrod was deemed extinct in 1921 after two dams were built on North Carolina’s Yadkin River. In one case, the river scour plant grew abundantly in an exposed scoured site. The diminutive clusterhead was considered extinct after the last known population was ploughed up in 1987. However, a new population was discovered in 1994.

Many species that were threatened are doing quite well

In Australia, 26 species no longer need threatened listing, which includes the eastern barred bandicoot, greater bilby, burrowing bettong, western quoll, sooty albatross, Bulloo grey grasswren and Murray cod, Flinders Ranges worm-lizard, southern cassowary and Gouldian finch. Of course, many non-government agencies and researchers don’t like this as the gravy train of funding reduces.

Elsewhere around the world, the list of animals and plants rebounding to higher population levels is immense. Here are just a few examples.

Southern elephant population increases; golden eagles in Scotland at highest levels in 300 years; how the humpback whale made a massive comeback in the Salish Sea; Peregrine falcons, once extremely endangered, now stable in Iowa skies; UK butterfly numbers at highest level since 2019; lifeline for endangered insect feared extinct; prehistoric bird once thought extinct returns to New Zealand wild; Maine’s puffin colonies recovering in the face of climate change; record-breaking number of sea turtles found on Texas beaches; golden paintbrush delisted from Endangered Species Act; tiger populations grow in India and Bhutan; native giraffes make a return to Angola; record year for olive ridley turtles in Bangladesh; blue whales comeback as they thrive in Californian waters; seals are making a comeback in Belgium; 5,000 new species found in the Pacific Ocean; scientists discover 380 new species in southeast Asia; black rhino starting to thrive in Zimbabwe; deep-sea Galapagos reef teeming with life; oysters back from the brink in Brisbane; Uganda sees resurgence of rhinos, elephants and buffaloes; Mumbai embraces its booming flamingo population; gecko makes dramatic recovery in Caribbean; wolf population set to expand in California and Colorado; six new species of rain frog discovered in Ecuador; wolves and brown bears making comeback in Europe; ospreys make return across UK; wolf packs are spreading quickly across the Alps; parts of Great Barrier Reef record highest amounts of coral in 36 years; bighorn sheep reclaim former high plains in Nebraska; wild tiger population nearly triples in Nepal; bison are returning to the plains; rhinos return to Mozambique; greater one-horned rhino population reaches new high; brown bear population in Pyrenees highest in a century; a welcome comeback for Norway’s walruses; bitterns make booming recovery in UK wetlands; green turtles bounce back in the Seychelles; Siberian tigers return to north-east China; brown kiwi numbers swell to 20,000; beavers are thriving in Alaska; fur seal populations booming; Earth has more tree species than we thought; giraffe populations are rising; Florida County beaches see record number of sea turtle nests; New Zealand’s sea lions rebound; sharks are now living in the Thames; snail darter is no longer endangered; popular tuna species no longer endangered; Caucasian velvet scoter back from the brink; pine marten more numerous than previously thought; wildcats return to the Netherlands after centuries of absence; giant pandas no longer endangered; Arabian oryx population surges; white-tailed eagles appear on Loch Lomond for the first time in 100 years; Comeback on the Cards for Asian Antelope Declared Extinct in Bangladesh.

The false story of the emperor penguins – a case study into a real extinction scam blinded by climate change beliefs

Emperor penguins have achieved celebrity status in recent years thanks to popular films such as Happy Feet and the documentary March of the Penguins. The colony of emperor penguins shown in the documentary, known as Pointe Géologie, where the Dumont D’Urville Research Station is located, has been studied for over 60 years.

Since 2009, “experts” have told us that emperor penguins could be almost extinct by 2050. Because they raise their chicks almost exclusively on thick ice locked between islands or icebergs, commonly known as fast ice, they are vulnerable as rising CO2 levels and climate change lead to the breakup of the fast ice.

All of this, of course, is based on modelling not empirical data. After all, seabird ecologist at the Australian Antarctic Division Barbara Wienecke said:

“modelling suggested the iconic species faced virtual extinction…at the current rate, extinction is virtually a given”.

On the contrary, observations and scientific evidence reveal that emperor penguins are thriving, and numbers are increasing, as sea ice and Antarctic temperatures behave opposite to the model predictions. In 2009, estimated numbers of emperor penguins were between 270,00 to 350,000 adults, and the IUCN ranked the species as “least concern”. In 2012, the estimated number of adults increased to 595,000, yet the IUCN, due to pressure from climate modellers, non-government organisations and governments, recategorised the species as “near threatened”.

There has been some uncertainty associated with the population number estimates until researchers introduced a change in methodology. Using the satellite data, Peter Fretwell and colleagues predicted the number of penguins by faecal stains they left on the ice. They also discovered several new unknown colonies and nearly doubled the estimate of the world’s emperor penguins. It showed that penguin numbers were much more robust and were far more resilient to any form of climate change.

The broo hah over the conservation status of the emperor penguin began with a study by scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and an accompanying media release, quoting lead author Stephanie Jenouvrier saying the emperor penguins were marching towards extinction. The study focused on a well-studied population because it was near the Dumont D’Urville Research Station.

Jenouvrier wrote that:

“IPCC predict warm years will become warmer taking that into account, would only increase the probability of quasi-extinction [of the penguins]”.

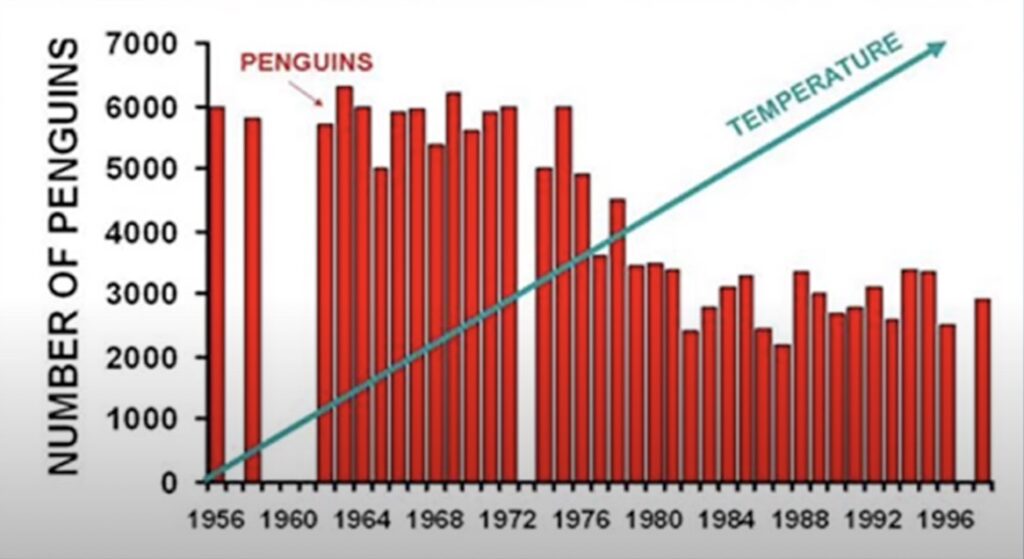

The graph to the right was on David Ainley’s website. It purportedly shows a connection between the penguin’s decline and rising temperatures. The numbers of emperor penguins were stable during the 1950s and 60s. Then, in the late 1970s, penguin numbers plummeted. Ainsley postulated this was due to rising temperatures associated with climate change.

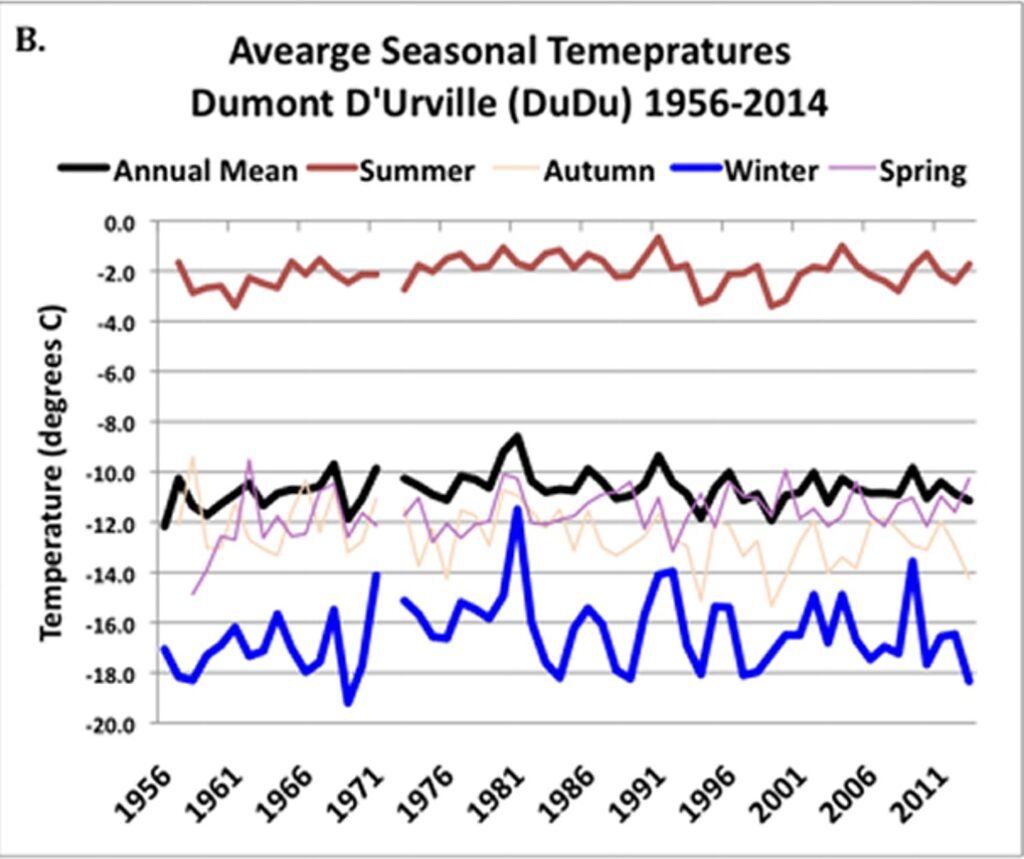

However, the graph misrepresented what was happening. Temperatures rose to 1980, but since then have cooled. Antarctica hasn’t warmed in 70 years, and only recently, a new cold record of 57OF below zero was set at Antarctica. Because of this, Ainsley removed the graph from his website. It is claimed that Jenouvrier and her colleagues, as well as the peer reviewers of their study, knew enough in 2009 to see that cooling trend.

Ainsley’s green arrow suggesting “steadily rising” temperatures is made up. The actual temperatures at Dumont D’Urville are shown below. When Ainsley was asked to justify his false representation, he said he intended to show a temperature trend but acknowledged it was wrong.

According to Jim Steele, Director Emeritus of San Francisco State University’s Sierra Nevada Field Campus, a better correlation to explain why penguin numbers declined at Dumont D’Urville Research Station was due to research disturbances that caused penguins to abandon the site.

Other studies on penguins, including this one on Adelie penguins, showed that attaching flipper bands to identify different penguins and determine how long they were surviving caused them difficulties in foraging. There was some variability in the results as some penguins with bands survived quite well. However, for affected penguins, foraging trips took 3.5 hours longer than non-banded penguins. Banded penguins also had more wear and tear on their flippers. Bands decreased apparent annual survival by 11-13 per cent during 200-2003.

Emperor penguins huddle together to conserve energy and heat in winter. The penguins were forced from their huddles to march in columns of twos so researchers could read the flipper bands. This is believed to be the reason why the penguins left that population.

Dr Michelle LaRue led a study in 2014, also using satellite imagery, analysing the shifting patterns of penguin poo, and her results prompted scientists to “unlearn” a critical belief that has supported speculation of the emperor penguin’s imminent extinction. They believed emperor penguins were philopatric, meaning they returned to the same location each year. Whenever researchers counted declining penguins at their study site, they assumed the missing penguins had died.

LaRue’s study showed other populations could suddenly double, thus challenging the notion of philopatry. The only reasonable explanation for unusual rapid population growth was that other penguins had immigrated from elsewhere, and claiming loyalty to a breeding ground was misleading.

LaRue’s study identified the appearance of freshly stained ice in several new locations, confirming her belief philopatry was not relevant. She said something very logical that escaped other researchers blinded by the climate change narrative:

“If we want to accurately conserve the species, we really need to know the basics. We’ve just learned something unexpected, and we should rethink how we interpret colony fluctuations”.

Indeed! What she was saying was scientists need to revisit how they interpret population changes and the causes of those changes.

Unfortunately, several true believers of the climate change narrative spun this evidence of an ancient behaviour into a new behaviour forced by climate change disruptions.

Mistaking unanticipated emigration for local extinction is sadly part of several similarly bad global warming studies. In 2009, a survey by scientists led to the argument that climate change had extirpated a missing Beverly herd of caribou, which once numbered 276,000. Scientists believed that the caribou always calved in the central barrens near Baker Lake. However, the herd was later found exactly where aboriginal elders said they would be. The herd shifted its calving grounds north to the coastal regions around Queen Maud Gulf.

According to Steele, Hal Caswell, a co-author of the Woods Hole Oceanic Institution emperor penguin extinction paper, mistakenly interpreted polar bear emigration as evidence of death due to climate change. He used his work to argue for the bears’ imminent extinction. He also modelled the extinction of the March of the Penguin’s Dumont d’Urville colony in 2009. Knowing they were wrong on that score, Caswell and his co-authors doubled down on that first prophesy and promoted a more calamitous continent-wide extinction scenario.

Lead author Jenouvrier summarised their study by saying:

“If sea ice declines at the rates projected by the IPCC climate models and continues to influence emperor penguins as it did in the second half of the 20th century in Terre Adélie, at least two-thirds of the colonies are projected to have declined by greater than 50 per cent from their current size by 2100. None of the colonies, even the southern-most locations in the Ross Sea, will provide a viable refuge by the end of 21st century”.

But her reference to the influence of sea ice on emperor penguins was based on the bizarre speculation in the widely quoted 2001 paper by Christophe Barbraud and Henri Weimerskirch. They argued there was an “early break-out of sea ice holding up the colony” without evidence. When asked by Steele for the dates when they observed the break-out, Barbraud admitted they were conducting analyses to investigate relationships between meteorological factors and breeding success, including dates of sea ice breakout. So, why did they make the claim in the first place, and how can unsubstantiated claims get published if a proper peer review process occurred?

The northward extent of sea ice has varied from 400 to 150 kilometres away from the colony, but any correlation to that movement is meaningless. The emperor penguin’s breeding success and survival depend solely on access to open waters within the ice. When the open water was within 20-30 kilometres from the colony, penguins had more accessible food access and high breeding success. When shifting winds caused open water to form 50 to 70 kilometres away, access to food was more difficult and breeding success plunged. Yet Barbraud and Weimerskirch argued that a reduction in sea ice extent, for unknown reasons, lowered the penguin’s survival. They used a meaningless statistical coincidence to speculate that catastrophic climate change was the main factor.

It is damning that the journal Nature even published Barbraud and Weimerskirch’s unclear analyses that can only be described as whipping up climate fear. But what is just as bad is that other scientists, such as Jenouvrier and Casswell, are using the study to predict more extinctions. Alarmist scientists seem to have monopolised the research funding to weaponise weather and natural penguin struggles to push a climate crisis narrative, which is odd considering what is happening in the field.

As a supplement to this story, Ainsley completely removed all reference to his and other’s work from his website regarding emperor penguins as he admitted that conclusions drawn “didn’t add up”. Adelie penguins are the only penguins now featured on his website.

Summing up

Despite doing their best to conjure a dire threat of widespread animal and plant extinctions by avoiding the scientific method, some scientists prefer to use models to estimate species loss. Professor Georgina Mace from the Imperial College in London believes the IUCN’s monitoring of species extinction rates is “helpful but inadequate and is never going to get us the answers we need”.

Perhaps using a mathematical model that can be manipulated to provide the answers “we need” does help.

Thankfully, other scientists have looked closely at the models. Professor Stephen Hubbell from the University of California says that an error in the models means that for years, they have overestimated the rate of species loss because they rely on the species-area relationship. The models calculate a more significant species loss if a large area suffers habitat loss.

Hubbell argues the models do not work in reverse. If a habitat increases by, say, five hectares, calculations show there are expected to be five new species. However, it is wrong to assume that reversing the model and shrinking the habitat eliminates five species. That is because it takes more area to show every individual in a species has been eliminated than it does to discover a new species. Hubbell says when corrected, models show about half as many species going extinct as previously reported.

Another problem is working out the background extinction rates or how many species would have gone extinct naturally. Background rates are not constant, and extinction rates vary a lot. Unsurprisingly, no one can be sure of the scale of species loss.

It is also not surprising that WWF supports the federal government’s recent announcement of zero extinctions in Australia and is supposedly reserving 30 per cent of land by 2030 to achieve that. State governments have converted millions of hectares of land into national parks since the 1990s. Conveniently, no baseline studies were done at handover to see if benign neglect doesn’t lead to worse outcomes, or if they have been done, no follow-up studies have been carried out. Therefore, no one knows if our current reserves prevent extinctions, adding to the problem, or indeed, are the problem.

The dire predictions in the 1970s from “experts” in biology and zoology that predicted “of all the species alive in 1970, at least 75 per cent would be extinct by 1995” have predictably not come to pass. Yet, we are expected to continue to believe the myriad of similar claims still being made in the scientific literature based on not gathering data but on modelling.

There is no solid evidence that we are headed for a sixth extinction event of our making. The idea that in the last 50 years, the variety of life on Earth has diminished faster than before is hogwash. Just because WWF makes these estimates doesn’t mean they have any validity and should not get any sensational media coverage.

So, as the world celebrates World Endangered Species Day, expect to be bombarded by media stories about the threat of significant extinctions, maybe even another story on the upcoming 6th global extinction event. I am confident you won’t read or hear stories where scientists are discovering new species such as this one where a record-breaking 815 species new to science were described in 2023.

Unsurprisingly, the media coverage will just report speculation without any substance.

Thank God (or whoever/whatever started the web of life) that the link between global warming and predicted extinctions has been debunked by the author of this paper.

A “mass extinction” is a concept that’s fairly irrelevant in human terms, because it’s the extinction of US which should be the primary concern. I am old enough to have been bored by people of my parent’s generation constantly banging-on about “Oooh – how I envy you young people today” way back in the 60s and 70s. I don’t think kids hear that today, which should tell anyone with half a brain that, as a species, we’ve reached (and passed) “peak humanity”. We/they still love them, but we’ve ceased to envy them. Humans are on a long, slow decline toward irrelevance as far as being controlling mechanisms of this planet are concerned – it’s just a case of which other furry or leafy co-residents of Earth they take with them as they continue to atrophy. Life started on this planet without the benefit of human “ingenuity” – I’m sure it will regain that pre-eminence again after we’ve had our go at messing things up. In universal timeframes we’re just a silly bunch of arseholes who got a bit too big for our boots. I’m sure we’re neither the first nor last in this Universe that’s ever held a moment’s sway over their surroundings and then lost the plot. Don’t believe me? – then open-up any newspaper you subscribe to and show me where humanity is “doing a good job”.