While researching for my three-part series on the truth behind the rainforest wars in New South Wales (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), there was a constant theme in the historical account of utilising one species of rainforest timber. While the cutting of hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamii) was undoubtedly very extensive in New South Wales, the scale of utilisation in Queensland was even more significant, and one of its primary uses was for butter boxes. To get an idea of the extent of the sanctioned over-cutting of rainforests during World War II, read my blog “Rifles, rainforests and rhetorical exuberance”, where I outline how foresters were forced to cut over 8 million super feet of Queensland maple (Flindersia brayleyana) in already depleted stands each year during the war for rifle furniture. Hoop pine was also over-exploited during this period.

The small but excellent historical museum at Kyogle provided some interesting but brief anecdotes about butter boxes. I thought I would write a story to learn more about them.

History of butter use

The Bible is interspersed with references to butter, the product of milk from the cow.

The earliest references to butter-making came from India, recorded in sacred songs of the Hindus about 2,000 BC. They shipped the butter from India to ports of the Red Sea. It has since been a staple for thousands of years. Butter is made using a simple process – separate cream from milk, churn it, and add salt. While the ancient Greeks and Romans ate plenty of cheese, they did not use butter very much. Those who did enjoy butter as a food in ancient times, such as Germany and other northern European countries, seldom used it fresh. The practice was to melt butter before storing it and use it in cooking rather than as a spread. Except butter in olden times was not the choice, flavoured product we know today.

When butter reached Athens and Rome, its flavour was anything but pleasing. They used it more as an ointment to enrich the skin and as a dressing for the hair. They also used it for skin injuries and considered that soot from burnt butter was good for sore eyes. As late as the seventeenth century, farmers sold butter as a cure-all. Its use as a cooling salve for burns and bruises has been practised throughout the ages. In the nineteenth century, butter was burnt as oil in lamps, particularly in Scotland.

Farmers often stored butter by burying it in the ground, allowing it to remain there for years. In years gone by, the Irish used to bury their butter in bogs, either to store it, to hide it from invaders, or to develop a flavour. The Irish acquired a taste for rancid and high-flavoured butter, and the Irish Hudibras (1689) supported this:

“Butter to eat with their hog, was seven years buried in a bog”

For early farmers, making butter was the opportunity to utilise surplus milk during lush periods and, through storage, for use during times of little milk production. It gave the dairy farmers security and farm stability.

Today, butter is almost exclusively used as a food product, and few of us would consider purchasing it for any other purpose. Its qualities explain its pre-eminence as a food fat – aroma and flavour.

The early development of dairying and butter making in Australia

For most of the nineteenth century, Australians relied on butter imported from England and Ireland in kegs, tubs and casks. As small dairy farms started in Australia, farmers stood their milk for long periods in wide shallow pans to allow the cream to settle on top. They then skimmed off the cream by hand, placing it in a vessel and churning it often using makeshift equipment. Churning was a form of agitation to get the small fat particles in the milk to unite to form butter granules. Churning took at least half an hour, depending on the quantity of butter fat and the day’s temperature.

In Europe, from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution, a churn was simply a barrel with a plunger that was moved up and down by hand. Making butter via such a vertical churn was tiring and usually involved two people – one to hold the churn and the other to operate the plunger until butter happened.

Butter makers in Australia were usually advised to make butter early in the morning when it was cooler and to try to keep the cream as cold as possible. The clumps of butter were then worked to squeeze out the whey, salted and then shaped. The amount of salt depended on the distance the butter had to travel. Since milk was unsterilised, the interval between butter production and sale to the customer had to be as short as possible. Early milking sheds were unsanitary, with earthen floors contaminated with cow dung. Milk containing high levels of bacteria was prone to sour quickly, especially when farmers could not keep it cold.

The local dairying industry slowly grew, and by 1890, consumers bought most of the butter from the local farms. The first dairy farms were small and only existed in areas cleared of forests. If the butter was salted, farmers made a satisfactory product.

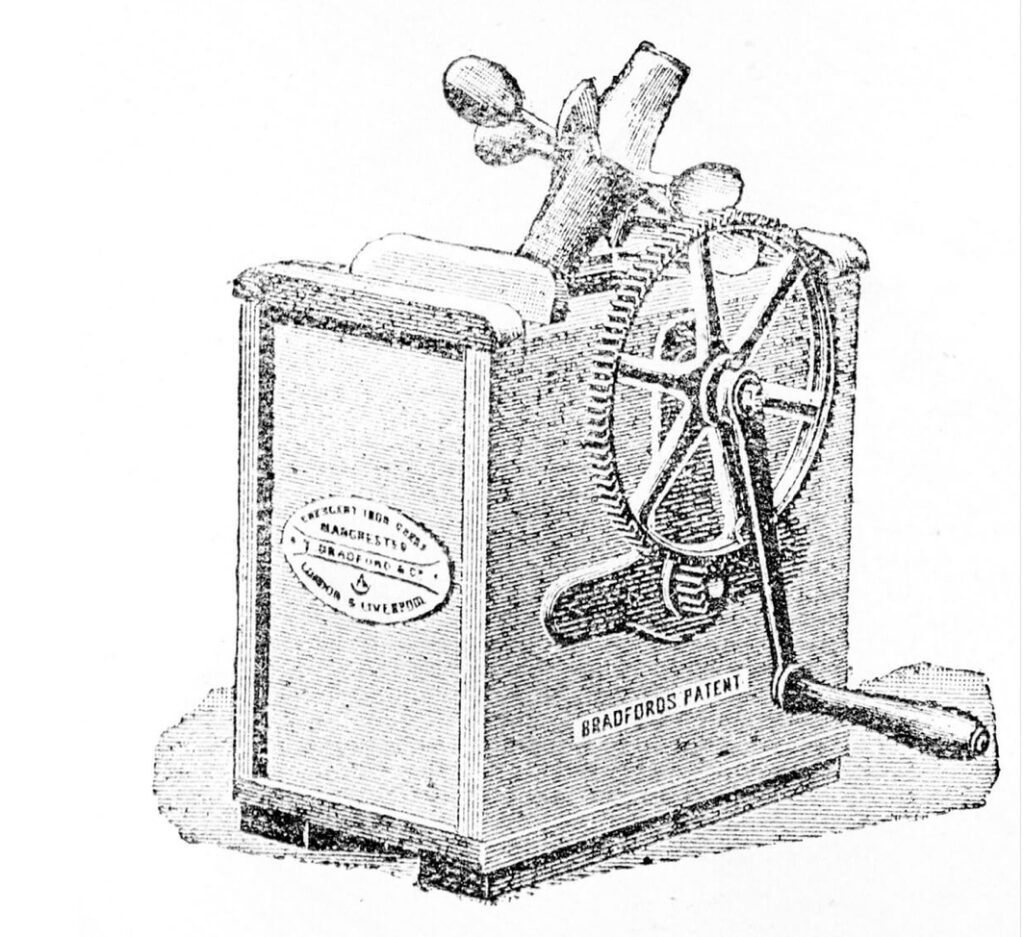

From the late 1800s, a number of crucial factors aided the expansion of Australia’s dairy industry by the interwar period. They included the introduction of mechanical cream separators in the 1880s; Babcock testing to accurately measure cream content in milk; and the Meat and Dairy Encouragement Act 1893 in Queensland which made provision for government loans to construct butter and cheese factories. The introduction of pastures such as paspalum and Rhodes grass and the increased cultivation of fodder also occurred, helping to improve milk yields and to provide adequate feed during the less productive months of winter.

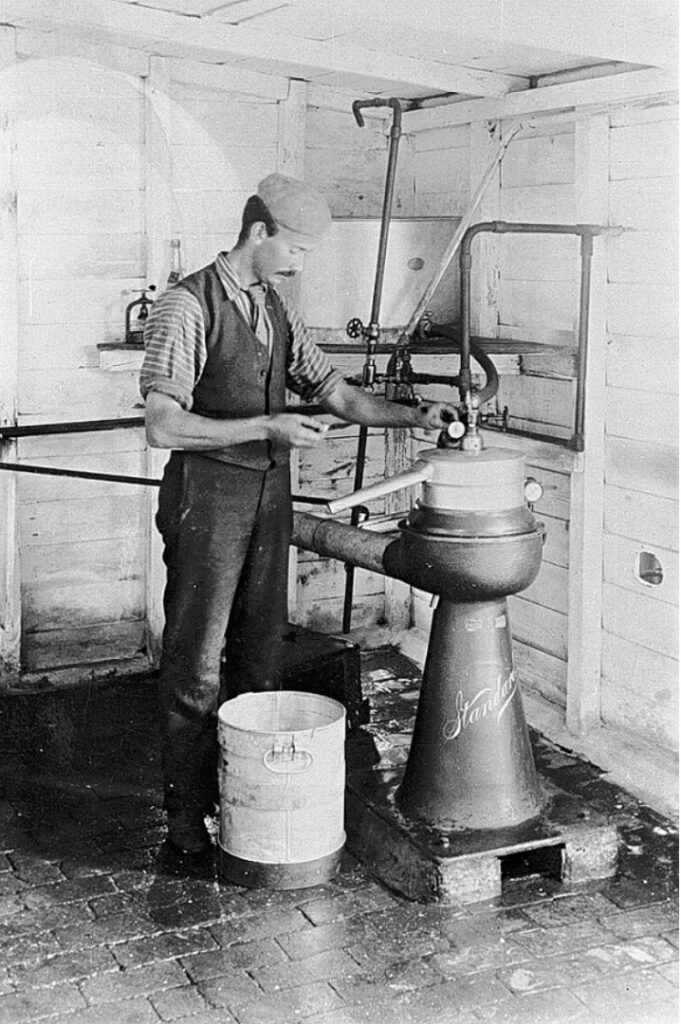

A significant change came in 1878 after Swede Gustaf de Laval was granted a patent for a milk separator, which permitted butter-making to begin as soon as the milk was received. Milk separation began in Australia in 1881, although the early machines were cumbersome, some being horse-driven. While farmers were now able to separate cream on the spot, if it accumulated on the farms in unrefrigerated storage, it readily deteriorated.

The dairy industry rapidly spread by establishing creameries to receive milk and butter factories. Most of the value of the milk was in the cream or milk fat. However, milk fat was a tiny fraction of the milk, usually between 3-7 per cent. Assuming all milk was equal was not a reasonable assumption. Just because one cow gave more milk did not mean that cow was making more money. Farmers needed to know the fat content of the milk so they could feed and manage their herd correctly.

In 1890, an American agricultural chemist, Dr Stephen Babcock, developed a test to determine the richness of milk or cream by measuring its butterfat content. He freely shared his invention with the world, and the Babcock test became universal.

The test was performed by thoroughly mixing a sample of milk, then via a glass pipette, 17.5 millilitres of the milk was placed in an eight per cent test flask. 17.5 millilitres of the correct strength of sulphuric acid was added to the milk and thoroughly mixed. The sulphuric acid dissolved all the solids, not fats, and generated heat, making the fat mobile and raising the milk serum’s density, thus rendering the fat separation easier.

The test flask was then added to a centrifuge and whirled for five minutes, separating the fat globules from the milk serum. The centrifuge brought the fat to the centre and the surface. Hot water was added to bring the liquid to the neck of the bottle to retard any further action of the acid. The centrifuge was again whirled for two minutes, adding more hot water. This brought the butterfat into the graduated neck of the bottle. The centrifuge was whirled for a further minute to bring all the fat into the neck of the bottle. The amount of fat was measured with a pair of dividers, and the butterfat percentage was read directly from the graduations on the neck of the bottle.

The rise of butter factories

There are many stories about how butter factories played a significant part in developing dairy regions nationwide. Before they were built, nineteenth-century dairy farming was small and serviced a local industry with few steps between the farmer and the customer.

But with the rise of industrialisation and the need for more hygienic practices to improve the quality of butter, milk and cheese for consumption, dairy production moved to factories owned by private companies and co-operatives.

Victoria rapidly became a major dairy area, and by 1895, there were 200 butter factories and 300 creameries. A strong export trade emerged, however, the quality of the butter and cream products was still not good enough. The poor butter quality wasn’t suitable for human consumption. The first Victorian butter sent to London was only good for axle grease. The colonial (later state) governments were forced to take action to introduce improvements.

They appointed Government dairy experts to advise the industry and assist in technology advances. Victoria appointed David Wilson in 1888. He immediately promoted separators and later introduced pasteurisation. He also appointed a chemist to lecture factory managers and butter-makers to help them improve their products for the market.

In the 1890s, the separator, the Babcock test, and the development of general factory utensils and equipment all combined to establish contemporary dairy technology. By around 1900, factory-made butter produced at the myriad of butter factories around the country was more common than homemade butter. It also replaced cheese as the major dairy product.

In Queensland in particular, purpose-built cream sheds following a standard design by Queensland Railway were constructed at stations and sidings along railway lines to cater for the expansion of the dairy industry. Special trains were organised to pick up the cream cans and taken to the railhead where they were then transported to the butter factories. After being washed, they were returned to the name inscribed on the cream can.

Refrigeration was an additional real game changer that assisted in developing butter factories, but it was expensive and initially concentrated only in large dairies and factories. The significant advantage of refrigeration was it allowed farmers to separate the cream on the spot rather than use the old pan method. Over time, it helped develop a reliable export industry. There was a network of butter factories with refrigeration, and railways also built cool rooms at stations in dairying districts. There was also refrigeration on fast steamers, which was important as Australia managed to supply the British and European markets when it was in short supply out of their season.

Butter boxes

When the butter was crudely churned, it had no defined shape or size as the farmer invariably used it in their household or sold any excess to neighbours or the public at markets. It then had to be cut into the desired size.

But when the factories began producing butter in commercial quantities, they began producing a standard size. A simple device made from wood and wire, a butter cutter cut a 9-pound slab (just over 4 kilograms) of butter into more manageable and saleable half-pound (just over 225 grams) blocks. Each half-pound block was wrapped in parchment paper for transport and sale.

The butter cutter was later replaced with large, electric machines that could cope with the dramatically increased factory output.

To transport the butter to various markets, factories looked for timber that didn’t taint the butter. Australian hardwoods were unsuitable because they contained tannins and oils known to taint the butter. Using a timber species that did not change the smell or taste of the butter packed inside was essential.

In Victoria, they looked to New Zealand’s tallest tree, the white pine or kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides). Because white pine timber is soft, pale and odourless, it was considered ideal for butter boxes.

Every three months, Victoria imported around 1,200 cubic metres of white pine from New Zealand. However, many white pine forests, which grew on accessible swamp lowlands, had already been cleared for agriculture. What remained was limited. As butter factories spread across New Zealand and export markets were secured, the country felled and milled what remained of this timber along the Waihou River.

New South Wales and Queensland mainly used Australia’s hoop pine, which grew naturally in rainforests in both states. Like New Zealand’s white pine, it was known to be non-tainting.

There was much controversy about the most suitable timber between the two species for butter boxes. The general opinion in Australia then was that white pine was the only timber that did not taint butter. However, they were more ambivalent overseas. The London correspondent of the Sydney Morning Herald wrote in 1906:

“It is not the case that buyers and handlers of colonial butter her, bother themselves at all about the wood of which the boxes are made. I speak in reference to the frequent statements in the Australian papers regarding criticism of the Queensland pine boxes. I have spoken about this matter to several practical men, and they tell me that no objection has been raised to the use of these boxes, and there is no evidence that can be got at here that butter packed in Queensland pine boxes is ‘tainted’ on arrival after its long passage. English buyers prefer a white box, and the Now Zealand kauri pine box would, if the point were raised, be preferred to the Queensland box, but the matter as regards this end of the business is of extreme insignificance”.

In 1903-4, the newly formed Commonwealth government increased the butter export business. Queensland expected it would obtain the lion’s share of the manufacture of butter boxes because of the suitable properties of hoop pine. By 1918, of the 25 million super feet of pine required annually in Australia for butter boxes, most of it came from Queensland. The Queensland export trade in butter alone required over 1.25 million boxes per year.

By 1920, as supplies of white pine dwindled due to an embargo of its export from New Zealand, the Queensland timber control authorities refused to make hoop pine available to Victorian butter box manufacturers. The Victorians were forced to substitute with hardwood. While possessing disadvantages, they believed they could meet immediate needs.

Western District Co-operative Box Company, which owned the butter factory at Warrnambool, bought abandoned agricultural land in the Otways and began harvesting mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) for a short period after a neutral coating of casein was developed to reduce the risk of taint.

Butter boxes were initially crudely made from wooden staves with nails holding the box together. They were continuously used until they fell into disrepair. They held 56 pounds (25.432 kilograms) of butter. As plywood manufacturing began, boxes were made with veneered wood, both band-sawn and rotary peeled and 3-plywood. They were strengthened by wire bindings. The machines used for stapling the box sides to the wire bindings were capable of producing 2,000 butter boxes every eight hours.

During World War II, veneer and plywood companies were declared a Reserve Industry. Munro and Lever at Grevillea on the north coast of New South Wales made boxes using 3/16th of an inch hoop pine plywood. They produced 48,000 boxes annually, supplying butter factories at Kyogle, Ettrick, Cawongla, Wiangaree, Casino, Murwillumbah, Tweed Heads and Lismore. The ply was cut to a specific size to make up the whole box, which had to be nailed onto a wooden frame about two by half an inch.

One of the problems with the boxes during shipment was they were stored on top of each other without allowing for adequate ventilation. Mr J D Dallas of Port Adelaide came up with a design by applying four half-inch thick strips of wood, two on each side and two on the bottom of the box, which allowed a good current to pass around every package of butter in the box. He also put a small hole in one side of each box with a cork so that the ship’s stewards could check the temperature of the butter without having to force open the top of the box.

Hoop pine utilisation

E H F Swain described the uses of hoop pine in his book, The timbers and forest products of Queensland:

“The pine is evenly grown, with only the mildest of growing differentiations. It is a firm, strong and fine textured coniferous softwood of the Kauri type…It has considerable toughness, but easy to cut, saw, nail, dress, glue, stain and polish, and is non-aromatic and tasteless…The hoop pine is particularly good for plys and veneers. Hoop pine is also used in the planking and decking of boats and small vessels, and with its absence of aroma is the wood par excellence for butter boxes”.

As early as 1920, there were the first references in Queensland to the “grave limitations of the hoop pine forests – the chief wood asset of Queensland – the basis of its timber trade”. The major areas where hoop pine was harvested were the Yarraman, Nanango, Kilkivan, and Gympie areas. Sadly, the destruction of areas set aside as timber reservations was advocated as necessary for the agricultural development of those districts.

The new Forestry Department raised a counter argument against permanently clearing hoop pine stands, stating that there were only 643 men employed in butter factories compared to 4,306 men employed in sawmills. Without hoop pine, the butter industry could not ship its produce to market.

The research and diligence of forestry officers proved that regrowing hoop pine could succeed after an initial common belief was that “reafforestation was not a success in [hoop] pine because it will not grow fast quality timber”. They successfully sowed seed in nurseries, tended the young plants carefully and transplanted them to the field at the opportune time. There were pine nurseries at Yarraman, Benarkin and Blackbutt. The tubed seedlings were planted in rows.

However, that was the least of their problems. In 1929, the butter box trade in Queensland was worth £80,000 to the sawmilling industry. But that year, the future of the trade was threatened. There was talk of tainted butter caused by the hoop pine boxes. Southern states that used New Zealand white pine were loud in denouncing hoop pine as a contaminant. It was not the first time the matter was raised. Timber taint by hoop pine had been mentioned periodically since 1905 when the State Dairy Expert recommended that pine for the boxes be well seasoned to alleviate the problem.

The Queensland Forestry Board took immediate steps “to test the complaint and locate, if practicable, the reason for the existence of wood taint in the year’s output, however small its proportions”. The investigation narrowed the source to hoop pine or white pine. Tests were carried out on the moisture content of samples of both woods. In the initial test results, lack of seasoning, the inclusion of ‘sinker’ pine (“dark-brown odiferous heartwood”) by unscrupulous millers and air pockets in the boxes causing butter oxidation were suspected. They considered that better methods of papering the butter would reduce the incidence of taint.

Although the committee boasted that “no timber produces any more satisfactory results than properly seasoned Queensland pine (hoop pine)”, research into the problem continued. In 1933, a policy was issued stating that hoop pine butter boxes were to be sprayed with a casein formulation to prevent taint.

Before World War II and more so afterwards, the end of Baltic pine imports used for linings and flooring created an enormous demand for hoop pine to fill the void. Government estimates in 1937 indicated that approximately 8,000,000 super feet of Queensland hoop pine was available annually to manufacture butter boxes.

However, due to the unavailability of white pine and a suggestion that supplies of Queensland hoop pine may be exhausted in ten years, the Department of Commerce proposed experimenting with boxes made from wood fibre compositions.

In New South Wales, the Forestry Commission carried out trials of hemlock for butter box manufacture. In the end, they decided that for any development of any softwood plantation project, it was essential to grow species of timber that would have as wide a range of uses as possible, with case timber as a secondary consideration. Plus, hemlock was not regarded as a building timber. The hoop pine plantations established on the north coast were intended for butter boxes as soon as thinnings were available.

Summing up

Hoop pine was a much-maligned species used in making butter boxes. From purely a physical attribute of the timber, it was superior to white pine. Hoop pine had the following features white pine lacked, which made it an ideal timber for export butter boxes – it is reasonably dense, tough and robust, rarely splits, and stands any amount of rough usage in transport without damage.

As for accusations of hoop pine tainting the butter, experiments showed hoop pine matched white pine in that regard every time somebody investigated it.

Hoop pine was heavily exploited in the state, which is unsurprising as it is a world-class timber species. However, it is fascinating to learn more about an industry where, yet again, one of our native timbers played a significant role in its success.

As for butter production in Australia these days, many argue that it has come full circle and the offerings on the supermarket shelf are a return to a rancid product due to poor quality ingredients. Apparently Australian cream is a by-product of the skim-milk powder sent to Asia and the Middle East.

According to Vue de Monde’s Shannon Bennett:

“No care is taken with it [the cream]. The butter we get at the end of that process is just rubbish. Australians don’t know what good butter is because we don’t make much [of it].”

Many of the top restaurants in Australia only use French butter because it has less water as too much water makes it hard to cook with.

Isn’t that a shame?

Fascinating research Rob. I spent some time in the Hoop pine plantations while studying forestry at Gympie. I’ve often thought the program seemed a hard and slow way to grow timber and wondered what drove the establishement of the hoop pine plantation estate. Still a beautiful and useful timber resource. Perhaps “heritage butter” stored in hoop pine timber boxes will become trendy one day and make a comeback!!

Thanks Rob for this interesting read.

I remember many years ago, as a very young kid, my Mum would apply butter to any burns my sister and I received. Even sunburn. I am not sure if it was effective or not (most likely not) but it was the “burn cream” of the day back then.

My Grandfather, Arthur Lawrence Leask, was the General Manager of the huge Cooperative Box factory on the part of the Sydney Harbour called Chiswick Point. The complex made butter boxes for the industry and I believe it was owned by the Dairy Industry. It was a huge factory employing large numbers of men and it occupied the whole of Chiswick Point.