I have spent decades in our wonderful forests, witnessing their cycles of destruction and regeneration, and in all that time, I’ve seen one constant: public perception remains stubbornly fixed on a false image of forestry. Headlines scream of devastation. Activists show photos of freshly logged areas, convincing the public that this is a permanent state. But they fail to show the next chapter—the regrowth, the renewal.

Through all that misinformation, whenever I had an opportunity to host a tour of visitors to the forest, I managed to peel away the lies and fabrications and show firsthand the truth about professional forest management and the benefits it brings, not only to the forests themselves, but also to society.

The media’s role in shaping misconceptions

The media are good at promoting anti-forestry viewpoints without critically examining the validity of those claims.

As such, foresters have always struggled in the court of public opinion. This is mainly because people make assumptions based on headlines, stories or images that are skewed to meet particular agendas, or what they hear from friends and work colleagues. It is easy for the media to sell a story about destruction using powerful imagary of a felled forest juxtaposed with a soft, cuddly koala.

You never hear or read a story about regeneration, of forests thriving under careful management.

Foresters struggle to have a voice that triumphs over the misinformation, lies, hysteria and the confected moral high ground.

While forestry practices have significantly improved over the years, this has largely been unrecognised. Unfortunately, forest management is politicised and criticised without documented reasons, which has led to vilification for no reason.

Not only does the media fail to participate in community education about forestry, they actively promote the views of those opposed to using forests for their timber products.

Repeatedly, we have had to respond to stories that malign our practices. When we tried to get on the front foot and be proactive instead of reactive, the media rarely took us seriously.

The dynamic nature of forests

The concept of “balance” in forest ecology is a myth.

What the media, and much of the public, fail to grasp is that forests are not static. They are living, evolving ecosystems that thrive on disturbance not stability. This is particularly true for our tall, wet eucalypt forests that require rejuvenation to survive. They have evolved to depend on severe disturbances like fire to regenerate. Without these disruptions – whether natural or managed – these forests would slowly die out.

Tasmanian botanist and some-time environmental activist, Jamie Kirkpatrick, is one of the few on the other side of the fence that understands the conundrum. He coined the term “hot fire paradox” to explain how the tall eucalypts in the wet southern forests are doomed to death by rainforest in the absence of fire and doomed to death by fire, if fire is too frequent.

This delicate balance requires active management, not neglect.

In the late 1980s, a photograph taken by environmental activist and professional photographer, Rod Blakers, became infamous.

Taken shortly after logging and burning, it showed a desolate, blackened landscape. The image was used widely by environmental activists as a symbol of destruction and greed. Yet, less than a decade later, the same coupe was a healthy young forest, teeming with life and lush with generating trees.

The series of three photos below, taken from the same vantage point used by Blakers, show a sequence from 1989 to 2006.

The logging coupe is in southern Tasmania known as Picton 39A. It was 45 hectares that supported mature stringybark or swamp gum (Eucalyptus obliqua) on the western side of the Picton River – a short river that begins near the south coast of Tasmania and flows north to join the Huon River near the major forestry visitor attraction, the Tahune Air Walk.

The first photo is graphically disturbing. It was taken shortly after clear felling logging occurred between June 1986 to June 1988. The coupe produced nearly 10,000 cubic metres of sawlogs and over 20,000 tonnes of pulpwood. In the spring of 1988, it was prepared for burning, and in March 1989, a high intensity regeneration burn was carried out.

Three weeks later, stringybark seed was aerially sown over the coupe.

If the forest remained the same as the first photo, then we would have a problem. However, less than a year after the burning operation, the first regeneration survey took place. It found 74 per cent stocking rate of young eucalypt seedlings, and a significant number of non-eucalypt species such as celery top pine, myrtle, leatherwood, sassafras and blackwood.

The second photo shows the profuse regeneration five years after the high intensity burn. By 2006, the third photo shows the area supporting a healthy and diverse young forest.

The foresters involved in managing Picton 39A are very proud of the outcome of the logging operation and subsequent regeneration. They played a vital role in protecting the eucalypt forests in this area.

The District Forester at the time, John Traill, believes protesters are ignorant of the ecological processes because they believe the forests are in balance, and logging tips the balance towards an ecological disaster.

Except, eucalypt forests don’t work that way because they are a very dynamic system, always changing. It is perplexing for a forester to see protestors put so much effort into protecting a mature forest of dead and dying trees that is in desperate need for renewal to sustain itself. Without any rejuvenation from either wildfire or clear felling and burning, the tall eucalypt species in these forests will die.

A lot of people fail to understand that these magnificent forests, called mixed forests because they have a well developed rainforest understory, are at great risk of disappearing in the absence of a major disturbance.

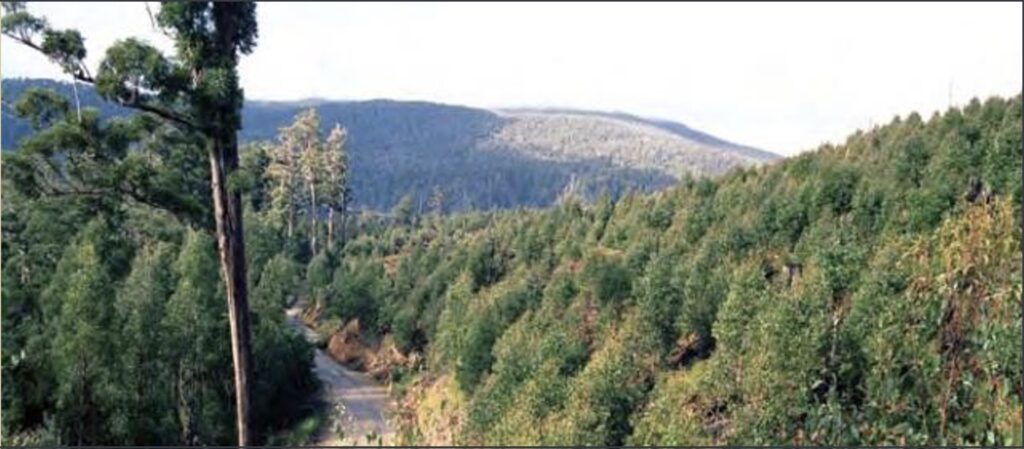

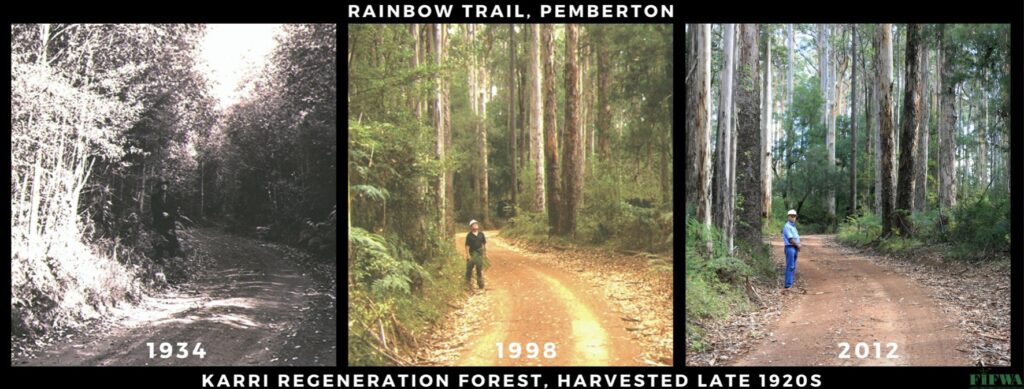

Here is another example from the karri forests of south-west Western Australia.

The sequence of three photos above were taken at the same spot on Rainbow Trail in Big Brook forest near Pemberton nearly 80 years apart. The road used to be an un-named railway where wood-burning locomotives hauled giant karri logs through the forest to the State Sawmill at Pemberton.

The karri forest was harvested in the late 1920s and regenerated in the summer of 1929-30 using a hot burn. Karri seed germinated soon after the first rains in autumn 1930. The far left photo shows the four-year-old regeneration. The young saplings eventually grew into the tall trees shown in the far right photo where they are over 50 metres tall. Green activists call this forest old growth, an anthropogenic term to signify a pristine forest that has never been touched by humans. Except it is not.

They cannot fathom that just under a century ago, a forest that was heavily logged with the large mature trees removed and a pile of vegetative rubbish left to be treated and burnt in a fierce fire, could become the scenic wonder they so cherish today.

Foresters as Conservationists

Foresters have always seen themselves as conservationists, even if the public doesn’t. Our role is to balance the needs of society with the needs of the environment, to manage forests so that they continue to provide the timber products people rely on while maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem health.

Yet, too often, we are cast as villains in this story, portrayed as destroyers rather than stewards. It’s a story that needs to change. If more people had the chance to walk through a forest that has been logged and then regrown, they would see what we see every day: that forests are resilient, dynamic systems that can thrive under careful management.

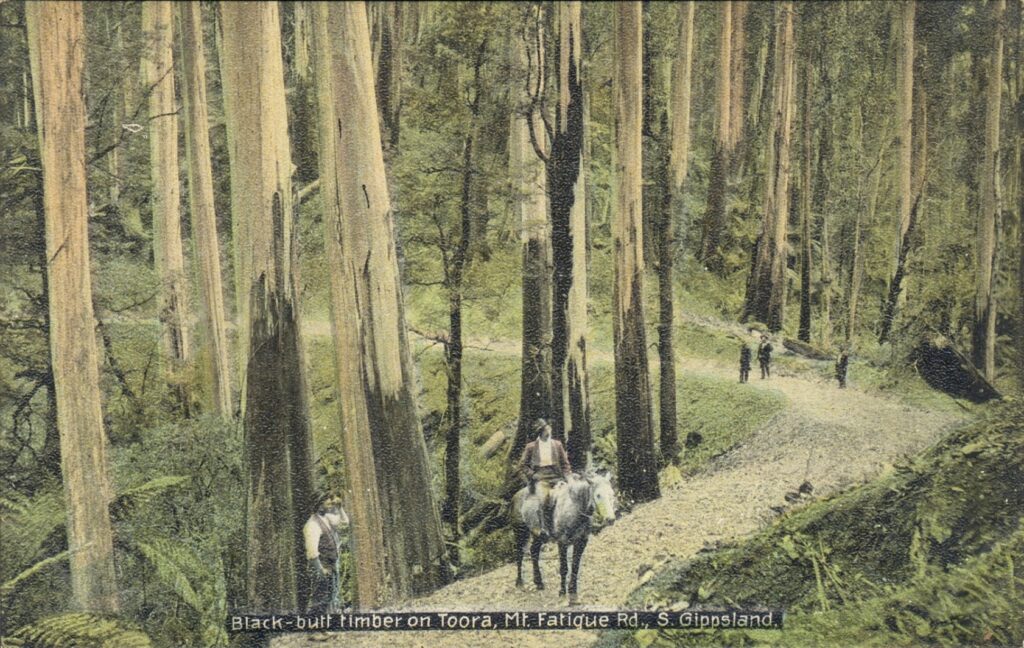

There are many examples of reserving areas of forest by foresters in the name of conservation.

A good early example is the Mt Fatigue area of the Strzelecki Ranges in Victoria. About 2,000 acres of mountain ash was set aside in 1882 for “growth and preservation of timber” after concerns from early foresters about the wastage of forests in the hasty, and ultimately failed scramble to settle the Strzelecki Ranges for farming. It is now called the Gunyah Rainforest Reserve.

Visitors to the magnificent karri forests in Western Australia are fortunate foresters recognised the scenic value of those forests around Pemberton in the late 1960s when the current activists were just a dream in their parent’s minds. They reserved the area and created a series of scenic drives, walking trails, picnic areas and interpretive information for forest visitors to enjoy.

A Day in the Forest: Changing One Mind at a Time

When I hosted visitors in the forest, I always found solace. It was my sanctuary and gave me confidence. I had the opportunity to show people first-hand the forests; explain how they grow; how they respond to disturbance; how we managed them; the silvicultural techniques; how logging operations worked; what we did to alleviate any impacts; how we protected them; how we kept them healthy; and how we maintained multiple values.

This was always effective.

But it was always to a limited audience, much more restricted than a dramatic nationwide story on Four Corners or the nightly news railing against forestry practices.

The ability to explain our practices in such an intimate group was very effective as it contrasted sharply with the articulate city-based professionals whose community status and easy access to the media gave them a perception of credibility, even if they never went to the forest, or when they did, it was only on the roads and walking trails. It only served to hide their lack of understanding of the scientific complexity of what they opposed.

One of my most vivid memories is from a day I spent with a city-based town planner. He was a classmate during our postgraduate studies, and he struggled with some of the environmental concepts. We struck up a bit of a friendship and I offered to take him on a tour of the forest to help him understand the realities of forest management.

We spent eight hours driving through forest after forest, from active logging areas, regrowth forests, and areas recently burnt. For most of the day, we drove on Horseshoe Road, which links the Nambucca and Bellinger Valleys. It is the main road through the coastal ranges and foothill forests and is 54 miles long.

By the end of the day, he was amazed – not by the devastation he had expected, but by the sheer scale and health of the forests. I will never forget what he confessed:

“I always thought we were running out of trees, but now, I see there’s so much more going on here.”

I assured him we only saw a small part of the state, and stands of forests primarily covered all the ridges and spurs of the valleys east of the Great Dividing Range. A fact not well known by the public at all.

His reaction was one I’ve seen many times. People believe what they see on the news—that logging is wiping out our forests. But the truth is far more complex, and once people understand how we manage these ecosystems, they begin to see the value in what we do as the true conservationists.

On the mid north coast of New South Wales, this issue was first raised in 1908. The Coffs Harbour Advocate ran a story proudly declaring the forests from Raleigh to Woolgoolga contained the finest hardwoods in the world, but they were under threat. It took foresters another decade before they could arrest the unwanton clearing of magnificent stands of timber and introduce effective management after conserving them.

A brush with fame

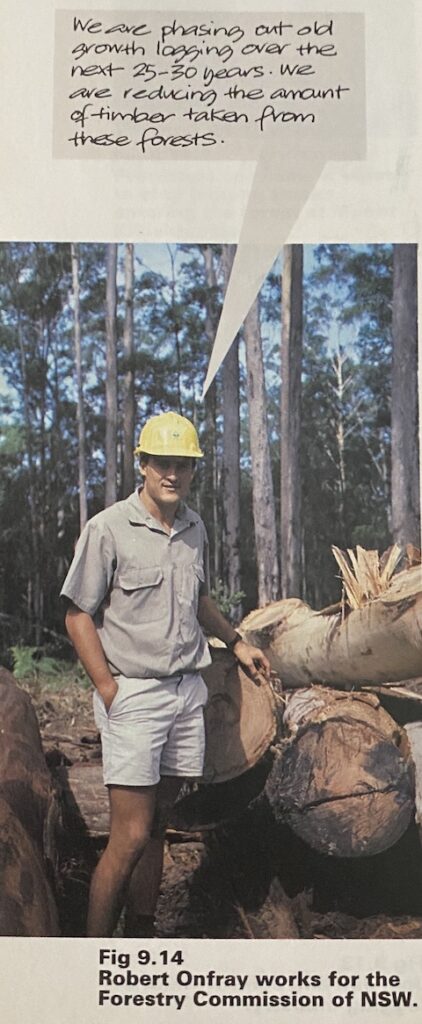

In the early 1990s, while I was working on the north coast of New South Wales, the fight over “old-growth” forests was building momentum. There were blockades in the forests right along the coast. We copped it as well when we planned to log the last mature compartment in the Bellinger Valley.

At the time, two authors who were writing a geography textbook for the New South Wales school curriculum, were conducting field trips to interview people living in communities and environments to feature in their book. They were very excited about the blockade we faced that was in the news at the time. They sought the views of both sides of the argument and approached me for the forest scientist’s view.

I took them to a coastal logging operation at Newry State Forest. They quoted me arguing our role in balancing the needs between preservation and the community’s need for timber and jobs. Although Newry was a regrowth forest, they asked me about the old growth issue. I explained the requirement for logging old-growth forests in the state while the coastal forests matured to maintain supplies to the timber industry and the eventual phase out of old-growth logging.

The logging contractor, Joe Mitchell, was also interviewed. He started working in the industry when he was 14 years old and, despite lacking a formal education, gave a blunt and considered message about how they were “bigger conservationists than what the greenies are”. He even provided a practical demonstration of the white ant problem in the butt of a log, explaining why the faller had to long butt the tree, which fascinated and bamboozled the two authors.

The Nature of Change: Forests Beyond the Surface

Mining engineer John Grover once remarked:

“real conservation is only possible because of the intensive production by miners, farmers and foresters”.

His point is clear: by maximising the intensity with which we use some lands, we allow others to be preserved. This balance offers the best chance to support support both our population and the environment.

However, many people view forests in a one-dimensional way, treating them as static, rather than dynamic living entities. What they see sticks in their minds. Chainsaws felling trees and 30-tonne machines tearing through the forests are not, in their eyes, a good form of stewardship.

This perception ignores the fact that such disturbances mimic the natural processes forests need to regenerate. An inconvenient truth for some is that many native forests actually require severe disturbance for their renewal. These are resilient ecosystems, constantly evolving through cycles of destruction and rebirth, not fragile sanctuaries in need of protection from all harm.

When foresters are allowed to practice without excessive interference, their ecological expertise ensures that when trees are felled, a new forest will emerge. It may not look the same at first, but just as people accept that a forest recovering from a severe bushfire or cyclone looks different, they must recognise that logged forests regenerate in their own time.

In fact, a patchwork of recently logged areas, young regrowth, mature stands and protected zones creates diversity, providing a range of habitats for wildlife. The range of animals found in actively managed forests, including arboreal mammals and birds that rely on tree hollows, is evidence that managed forests are anything but barren.

During my forest tours, I would often begin by showing visitors a freshly logged area. The sight was stark and brutal, harsh even. Then, I would take them to a nearby forest we had managed, adjacent to a picturesque pastoral scene of rolling hills, grazing cattle, and open paddocks. While soothing to the eye, this land was a permanently deforested landscape, supporting introduced, domesticated animals.

Next door, the state forest stood in striking contrast – lush, uneven-aged regrowth with a diverse understorey, including palms. A landscape far more appealing than the logged coupe. It’s no wonder sheer beauty of forests in an advanced state often fuels public support for their preservation.

After I pointed out that the forest had been logged 30 years ago and looked trashed immediately after logging, just like the logged area they had seen earlier, you could see the penny drop in their minds.

It goes to show that the ecological health of a forest cannot be judged by aesthetics alone. Is it fair to assume one can gauge the condition of a forest simply by looking at it? A doctor doesn’t rely solely on visual signs of distress to diagnosis a patient, and neither should we judge a forest by appearance alone.

The cost of stopping professional active management

But all that means little in the broader scheme of things. The battle over the wise use of our native forests is virtually over via a thousand cuts of ever increasing impositions designed to make forest management unviable.

Victoria and Western Australia recently ceased logging in native forests, a decision made under the mistaken belief that preservation is the key to conservation. This decision will have dire consequences, not only for the timber industry but for the forests themselves. Without active management – the careful balance of logging, burning and regeneration – those ecosystems will become stagnant, choked by overgrowth, vulnerable to disease and wildfires.

Our native forests managed for timber have a range of conservation values despite repeated logging events. It further reinforces that active management involving the application of principles mimicking disturbances that our disclimax forests require is a proven way to maintain their values.

What the public don’t understand is that stopping native forest logging doesn’t mean an end to the demand for specialised timber products. Either they do not use any products made exclusively from this timber in favour of inferior non-renewable sources, or instead, we’ll simply import more wood from countries that do not have the strict environmental controls we do.

The demand for wood with particular strength, durability or appearance features will always remain strong. Materials such as flooring, cabinets, benches, stairs, furniture, musical instruments and outdoor applications fit that bill. We cannot get those high-quality timber products from quick-growing plantations economically. They do not develop the features of our hardwoods in a shorter time frame.

It’s a paradox—by halting logging in Australia, we risk causing more environmental harm elsewhere or support imitation industries that are much more energy intensive.

That is of little consequence to urban Australians who ignorantly consume products from native forests. They see timber products every day. They use them every day. But they fail to make the connection that those products come from trees. Trees store carbon and are the ultimate renewable resource. Our well-managed native forests supply many of the timber products used by society.

Imagine a material so technologically advanced that it is self generating, infinitely renewable, requires no attention, maintenance or capital investment, comes in thousands of varieties, has almost infinite uses and is produced in the world’s largest factory whose pollution control is so effective, that its only by-product is oxygen … no its not something from science fiction … Its wood.

Nicholas Dattner advertisement in the early 1990s articulating the benefits of timber.

Rewriting the forest’s narrative

As a forester, I’ve often wondered if things might have been different if we had taken a more active role in telling our own story. If every forester had been trained as a tour guide, had taken the time to show people firsthand the complexity of forest management, perhaps the public would have a different understanding of our work. Perhaps we wouldn’t be on the verge of losing the battle for the future of our forests.

But there’s still time to rewrite this narrative. Forests are the ultimate renewable resource, and with the right management, they can continue to provide for both society and the environment. It’s up to us to tell that story.

Instead of listening to the media or an ignorant forest activist, why not head into your local forestry office and demand a forester take you on a tour so you can learn about what really happens in a forest and to show you that sustainable forestry isn’t about destruction; it’s about regeneration.

Another timely article and message.

Please send to FA to get promoted in their platforms.

By the way, the absence of PPE is disappointing but I suspect you did not want the apparel to mask your svelte form!

Well written Robert.

In my 19 working years in forestry, I had the same experiences.

One day, late in that time, I was confronted by a TV crew at an anti logging blockade in a Tasmanian State Forest in the Huntsman area behind Deloraine.

The activists had planned this for some time and caught the true conservationists off guard. It was not a good memory, and it wasn’t long after that that I moved to the agricultural/horticultural industry.

In hindsight, we were not trained to effectively rebuff the greenie approach and their blatantly wrong statements, and I felt intimidated.

And it still goes on today – a coupe in the Dial Range is a case in point.

Foresters understand that no forest existent today has not arisen from some major perturbation in the past.

The mob cannot easily appreciate the unrelenting power of forest regeneration.

Heads shake in disbelief that the superb spotted gum pole stands at Glenbar arose in cleared grazing paddocks from the lignotuber pool. Similarly, the ‘old growth’ blackbutts on Cooloola National Park that were given a heavy ‘haircut’ by my father 65 years back.

Pristine activists only need to use a single frame at logging to convey a sense of holocaust/doomsday.

The regeneration story takes multiple frames over time, as you have excellently illustrated and described in your article Robert.

More power to your quilling arm!

Well done, as usual, Rob.

The opinion that counts politically is that of city dwellers, who NEVER venture off the concrete footpath outside their houses (assuming, that is, that they actually stop sitting in front of their TV).

Maybe the timber industry needs to persuade the group who write the “Bluey” TV series to take up your case. Getting kids to believe in you will eventually succeed.

Really well written and argued, thanks Robert!

Good article Robert.

We foresters are not dismayed by seeing a clearfell. In our minds eye we see the area 100 years post that event.

Unfortunately the public can’t or won’t. Regards Frank

PS. I have photos taken in 2024 of Mundlimup jarrah clearfelled about 1882 and regenerated 1884. The area has been thinned twice and protected from wildfire by foresters.

Thank Frank. Unfortunately, we can’t embed the photos with the comment. If anyone wants to see the photos Frank provided, let me know.

I think you underestimate the abilities of the environmentalists. At the height of the woodchip arguments in the 1970s and 1980s, I conducted many tours of the forest. On the way out to the bush in the morning I had to explain that the white ones were karri. On the way back that afternoon they were telling me how it should be managed.

But you are right. For the most part field trips were positive – at least understanding why things were done even if not always agreeing.

As a consultant to the Water Corporation’s Wungong catchment water and environment program, we established several “demonstration plots” one hectare in size, thinned to various basal areas in 80 year old native jarrah forest. These were 50 (unthinned), 25, 18, 10 and 5 m2 per hectare.

We did the same in 18 year old bauxite pits rehabilitated with jarrah/marri. These were 0.5 hectare in size and each had 1,800 (unthinned), 650, 350 and 125 stems per hectare.

We also compared cut-stump treatments and notching with herbicide to gauge visual impacts.

Over several years, about 1,100 persons visited the sites, ranging from politicians, deep greens, EPA staff and foresters. We discussed timber yield, regeneration, protection, water yiield, aesthetics, biodiversity and forest health aspects of the various treatments.

Feedback was mostly positive …. and if not: “we still can’t agree with thinning, but at least we now understand why it is done and how it looks at various tree densities”.