Sydney’s early water woes

Since European settlement, Sydney has faced frequent water crises due to unreliable water supplies.

The first water supply for Sydney was Tank Stream, named for the “tanks” or reservoirs cut into its sides to save water. The stream, which wound through the early settlement, eventually degenerated into an open sewer and was abandoned in 1826. Subsequently, water carters sold barrelled water from the Lachlan Swamp, which later became Centennial Park.

In 1825, an inquiry was held to find a source of permanent water supply for Sydney. Mineral surveyor and civil engineer John Busby selected the Lachlan Swamp, part of a chain of swamps known as the Botany Watershed.

Convict labour was used to build Busby’s Bore, a 3.6-kilometre tunnel through sandstone to a reservoir at the Oxford Street end of Hyde Park. Although work started in 1827, progress was slow. By 1830, water was flowing in the tunnel, though it wasn’t completed until 1837. This bore could supply up to 1.5 million litres of water daily for Sydney’s 20,000 people.

However, the drought in 1838 demonstrated the limitations of Busby’s Bore. By 1852, water quality and quantity issues necessitated another solution, leading to the Botany Swamps Scheme in 1859. The scheme operated until the late 1880s, when the Upper Nepean Scheme was developed.

By 1867, Sydney’s population had outgrown the Botany Swamps’ supply. Early settlers knew little about conserving or storing water, coming from regions with continuously flowing rivers and year-round rainfall. Governor Sir John Young appointed a Commission to recommend a future water supply. In 1869, the Commission endorsed the Upper Nepean Scheme, designed by Edward Orpen Moriarty.

Over a decade passed, and another inquiry was held before the Upper Nepean Scheme was confirmed as the best solution to Sydney’s water needs.

The idea was simple and far-sighted – collect water in the Southern Highlands, where it rains frequently and heavily and transfer it to Sydney to provide a reliable supply.

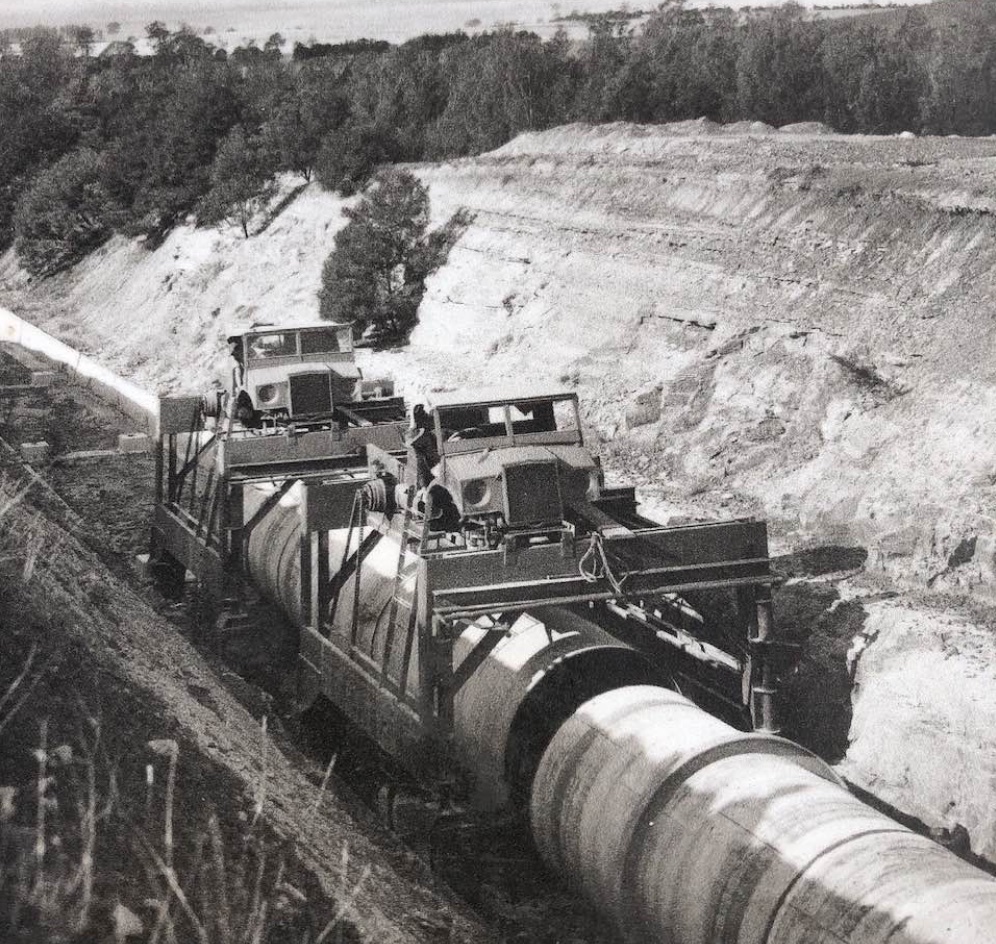

Construction of the Upper Nepean Scheme began in 1880 and was completed in 1888. It was a significant engineering feat, involving two weirs on the Cataract and Nepean Rivers to collect water delivered by gravity through a series of tunnels, canals and aqueducts to a large reservoir at Prospect, and deliver it to Sydney.

In June 1885, during a severe drought, the Upper Nepean Scheme was incomplete, and Sydney faced a critical water shortage. The Lachlan and Botany Swamps had barely ten days’ supply left. The Government accepted an offer from the Hudson Brothers to deliver three million gallons of water per day into Botany Swamps by connecting the gaps between gorges bridge with timber fluming. This became known as Hudsons Temporary Scheme, which operated until the Upper Nepean Scheme was completed.

When the Upper Nepean Scheme was finally completed, the Hudson emergency work was dismantled. The Scheme became the jewel in the crown of Sydney’s water supply, and it had to be expanded as soon as it was completed.

A decade after its completion, Sydney again faced water shortages during the Federation Drought in 1901-02. As the population grew, water shortages and restrictions continued. Fortunately, the Upper Nepean Scheme was designed for expansion. A series of dams in the Nepean area were built between 1907 and 1935, with the Cataract Dam being the first completed in 1907. Prospect Reservoir was an engineering feat at the time. It is Australia’s first earth fill and rock embankment, and still one of the largest.

However, throughout the 1930s and the early 40s, New South Wales was again in the grip of a water supply crisis, leading to plans for a more reliable water supply system, including the Warragamba Dam.

Planning one of the greatest engineering feats of the 20th century

Sydney continued to face an emergency water crisis during World War II and into the late 1940s due to repeated droughts. An interim emergency scheme, including a weir and pumping station on the Warragamba River and a pipeline to Prospect Reservoir, began operating in 1940 and was used for almost 19 years until the Warragamba Dam was completed.

In 1845, explorer Count Paul Strzelecki noted the Warragamba River gorge as an ideal dam site. Official plans to build a dam in the area date back to 1867 but were deferred during the Upper Nepean dams’ construction.

The Warragamba River, running about 23 kilometres from the Coxs and Wollondilly Rivers to the Nepean River offered two significant advantages as a prime site for a major dam – a large catchment area and a river flowing through a narrow gorge. However, engineers were deterred by the site’s history of frightening floods.

In the late 1800s, the Burragorang Valley was identified as the best choice for a project to solve Sydney’s water problems. Water would be collected from the Wollondilly and Coxs River stream catchments, forming Lake Burragorang behind the dam wall. Even so, the dam required the latest technology and advances in engineering.

Building the dam

An intensive site selection process took place six years before construction began, culminating in the choice of a site a mile upstream from the original plan. The site offered a massive sandstone bed suitable for the dam’s foundations. Dr J. L. Savage, the eminent American dam design authority, confirmed the choice. Construction of Warragamba Dam was approved on 2 October 1946.

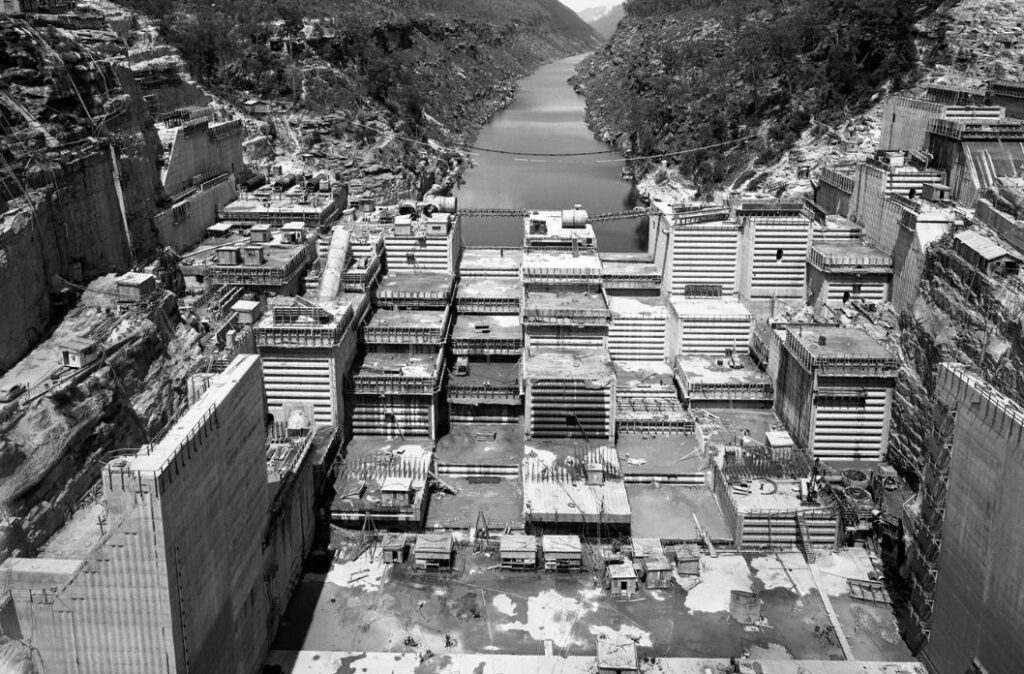

Work began on two temporary dams and tunnels divert the river and dry the construction site for excavation. More than 2.3 million tonnes of sandstone were removed.

The dam was built in a series of large interlocking concrete blocks using overhead cableways lifting 18-ton buckets to place the concrete. Concrete was mixed on-site using 305,000 tons of cement and 2.5 million tons of sand and gravel, transported from McCann’s Island in the Nepean River via a unique aerial ropeway.

For the first time in Australia, ice was mixed with the concrete to control heat generation during mass pours, preventing dangerous cracks forming. One of Australia’s first pre-stressed concrete towers housed the ice-making plant.

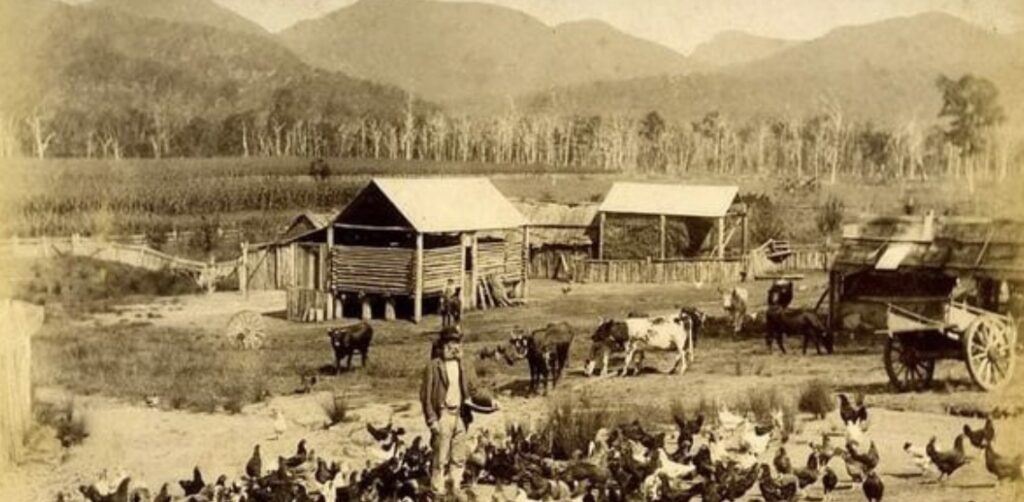

Residents in the Burragorang Valley were relocated. They were on rich farmlands that supplied vegetables for the Sydney markets. The Burragorang Defence League was formed to protest the relocation. They lost and were compensated. All buildings were sold by auction, with many relocated elsewhere.

The area to be inundated, more than 6,400 hectares of forest, was cleared so trees would not rot or float downstream to block the dam’s outlets and crest gates. The clearing cost $1.5 million and took years to complete. Where machinery could get to the timber, the merchantable logs were sold. On the flats, the timber was windrowed and burnt. The trees in tricky places on slopes were accessed by foot, felled by axe and crosscut saw and then inch-and-a-half holes drilled into them, filled with gelignite, shattering the tree into pieces large enough for the men to handle. They were stacked in heaps all along the gorge, ready for burning.

Up to 500 men were employed on the clearing. Contract labour camps were set up along the valley so that gangs of workers midway between Warragamba and Burragorang could camp on the job and save them the long trip by boat to and from the work site.

Pedestrian access between the Warragamba township and the work area was provided by two suspension bridges, one across Folly Creek and the other across the Warragamba Gorge just downstream of the dam. At the end of the project, one of the bridges was demolished, while the second one remained until 2001, when it was burnt beyond repair in a bushfire on Christmas Day. It was an exhilarating walk for visitors until the bridge closed in 1987 due to termite damage.

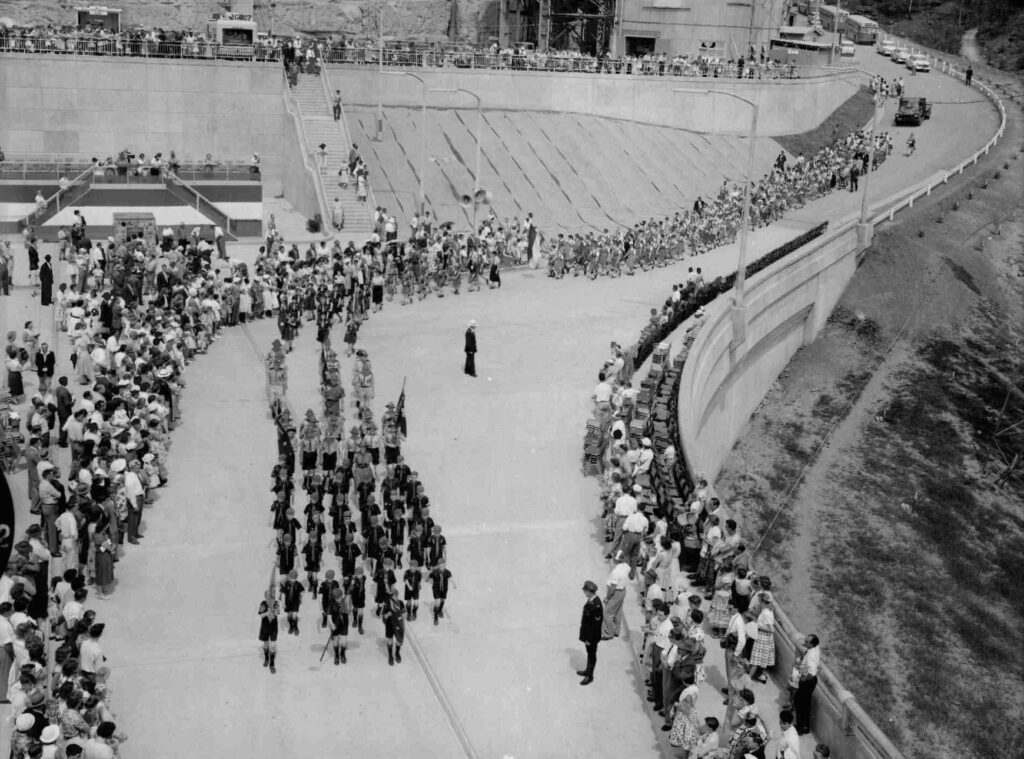

On 14 October 1960, on a beautiful spring day, Premier Bob Heffron officially opened the mighty Warragamba Dam, after 14 years of construction. During an inspection of the dam, the crest gates were opened releasing great streams of roaring water. After the ceremony the 1,000 official guests sat down in a former plant store to a lunch of oysters, lobster, chicken, ham and strawberries and cream.

At the start of the dam’s construction, it was estimated that it would take six to eight years to fill. However, with the number of floods in the construction years in the 1950s, the water level in the lake was kept at the lowest bay in the dam.

The size of the whole structure is considerable. The dam is 142 metres high and 351 metres long. The water it holds covers 75 square kilometres, making it four times larger than Sydney Harbour. 1,800 people worked three shifts a day, seven days a week and were housed nearby in the purpose-built township of Warrangamba. Homes, shops, schools and pubs were built in the remote location. It was planned to be demolished after the dam was built. However, many workers and their families did not want to leave when the project ended. They bought their little houses and stayed, and Warragamba township remains to this day.

A memorial was later built to honour the 15 labourers, carpenters, drillers and other workers who died in workplace accidents while building the dam.

How it all works

The best quality water is selected and drawn through screens at three outlets on the dam’s upstream face. After flowing by gravity to the valve house, two pipelines feed raw water to the Prospect water filtration plant, some 17 miles away and via off–takes to smaller filtration plants at Warragamba and Orchard Hills. The filtered water is then distributed to Sydney’s households, businesses and other users. A 14-foot diameter penstock operates a hydroelectric power unit at 50,000 kilowatt capacity.

The dam’s design includes five crest gates, a central spillway, dissipator training walls and an apron (stilling pond) to manage floodwaters and ensure safety. The auxiliary side spillway operates only in rare, extreme floods and diverts excess floodwaters around the dam.

Conclusion

Sydney had come a long way from its first water supply out of Tank Stream. Warragamba Dam is one of the world’s largest domestic water supply dams. It symbolises Sydney’s post-war maturity and resilience against droughts that plagued its water supply from the 1800s until the post World War II era.

Tremendous forces in play, aided by three million tonnes of concrete, hold back more than 2,000 gigalitres of water. The pressure behind the dam is, in effect, trying to push the wall down the valley, while water in the rock under the dam is trying to push it up. Thankfully, the designers considered these water and uplift pressures when designing this concrete gravity dam.

The completion of Warragamba coincided with the construction of the Opera House and the Snowy Mountains Scheme, a golden era in Australian engineering. The dam’s construction involved workers from as many as 23 different nationalities and played a significant contribution to the country’s proud multicultural identity.

Another informative and enjoyable read – everything a reader wants.

Brings back memories of my childhood, hearing about this amazing work and the people who built such places.

Thank you Robert.

Living history – thank you.

Narelle

Thank you Robert for this informative read.

I remember living in Sydney at the time of the opening of the Dam, and have always had a fascination with its construction.