In the heart of the Bellinger Valley, the Glennifer-Promised Land area is framed by a dramatic escarpment. This formidable landscape is defined by ancient, erosion-resistant rocks exposed from the Moonbil sedimentary beds, consisting of fine-grained siltstones, slate and chert. The escarpment forms a natural boundary, with the land dropping a staggering 970 metres from the plateau to the valley floor. The steep descent presented a significant challenge to those seeking to exploit the region’s rich timber resources.

Timber extraction in the Bellinger Valley began in the 1840s, with cedar cutters drawn to the lush rainforests along the rivers, creeks and major gullies. Cedar was a highly prized timber, and the industry quickly took hold.

The early timber cutters felled millions of super feet of cedar, though a considerable amount was wasted. As the accessible cedar stands dwindled, these pioneers turned their attention to cedar stands in other valleys.

This story, however, starts at the top of the escarpment when Michael Clogger settled at Bostobrick from the west in 1857. He opened up the Bostobrick Cedar Scrub, sending sawyers into the rainforests of the Dorrigo Plateau. There were valuable cedar trees, “many of which ran up for a hundred feet or more before the first branches”. Emerging from the gloomy rainforests after months of hard labour, sustained by only salt beef, damper, tea and sugar, they stood out from other bush workers by being “as pallid as corpses”.

Again, wastage was rife, and when faced with dwindling supplies, the timber cutters turned their attention to other valuable softwoods such as rosewood, coachwood, and hoop pine. However, getting their timber to market was a mighty challenge. Initially, timber was hauled to Armidale, a journey of 75-miles that took two weeks over primitive tracks. This route was particularly arduous and limited in its capacity to serve the growing timber industry.

While valuable cedar could justify the effort, other timbers needed a more efficient means of transport to reach the burgeoning coastal markets and the expanding rail and shipping networks along the coast.

In response to these challenges, a road was surveyed down the escarpment in 1876, following an old bridle track. The construction of the Dorrigo Mountain Road between 1882 and 1888 was a monumental task. The road was steep and unstable, often becoming impassable during wet weather. Even in dry conditions, a team of horses needed three days to deliver a load of timber to Bellingen.

By 1908, much of the accessible hoop pine around Dorrigo had been logged, pushing timber getters to seek new sources in increasingly rugged and remote areas. Attempts to reach these forests from Dorrigo proved fruitless.

The quest for hoop pine led to innovative solutions, including the construction of tramways and timber shoots, designed to transport the giant logs from the plateau forests to the valley, where they could be processed and shipped.

The Syndicate

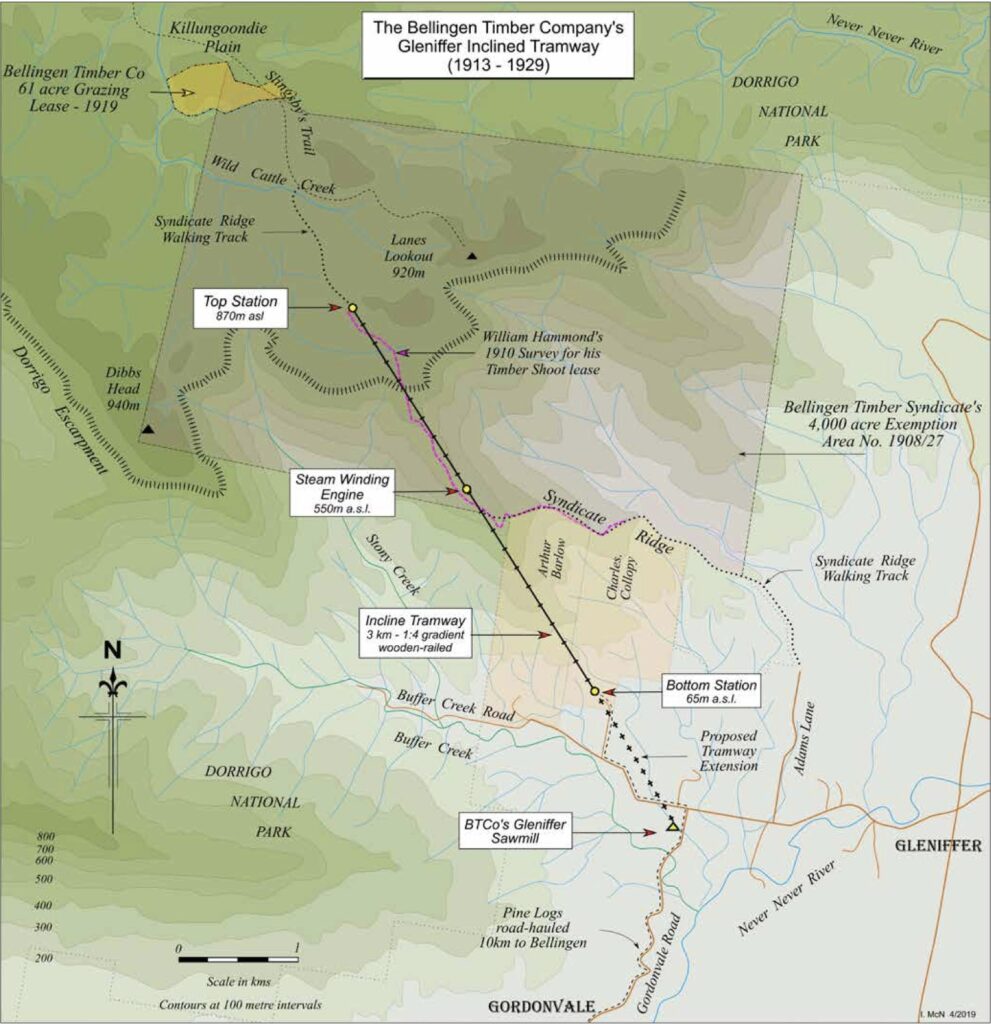

One of the more ambitious “pine lines” was the Syndicate Tramway, starting roughly halfway between Dibbs Head and Lanes Lookout down one of the main spurs to Glennifer. It was spearheaded by Bellingen businessmen William Hammond and Arthur Wheatley of Hammond & Wheatley Emporium fame.

They secured a 4,000-acre timber concession within the Forest Reserve north-west of Glennifer, on the slopes of the Dorrigo escarpment and over the top tapping into the valuable hoop pine forests.

The Syndicate faced the challenge of the steep and treacherous terrain, which included three steep ridges plunging into the valley. Local timber getter George Dillon, a seasoned expert familiar with the area’s geography, provided critical advice. Dillon, whose family were pioneers in the Dorrigo region, had an intimate knowledge of the hoop pine stands atop the mountain.

The Syndicate was granted a 10-year Special Lease to construct a two-mile timber shoot down one of the spur ridges. They partnered with Langdon & Langdon, a firm of Sydney timber merchants who required good quality hoop pine for their furniture business.

The newly formed Bellingen Timber Company (BTCo) had sufficient capital to invest in an incline tramway instead of a simple timber shoot. This decision was necessitated by the narrow ridge, where logs could easily veer off course and end up in the deep valleys on either side. The tramway represented a substantial engineering effort to safely bring the timber down the steep mountainside.

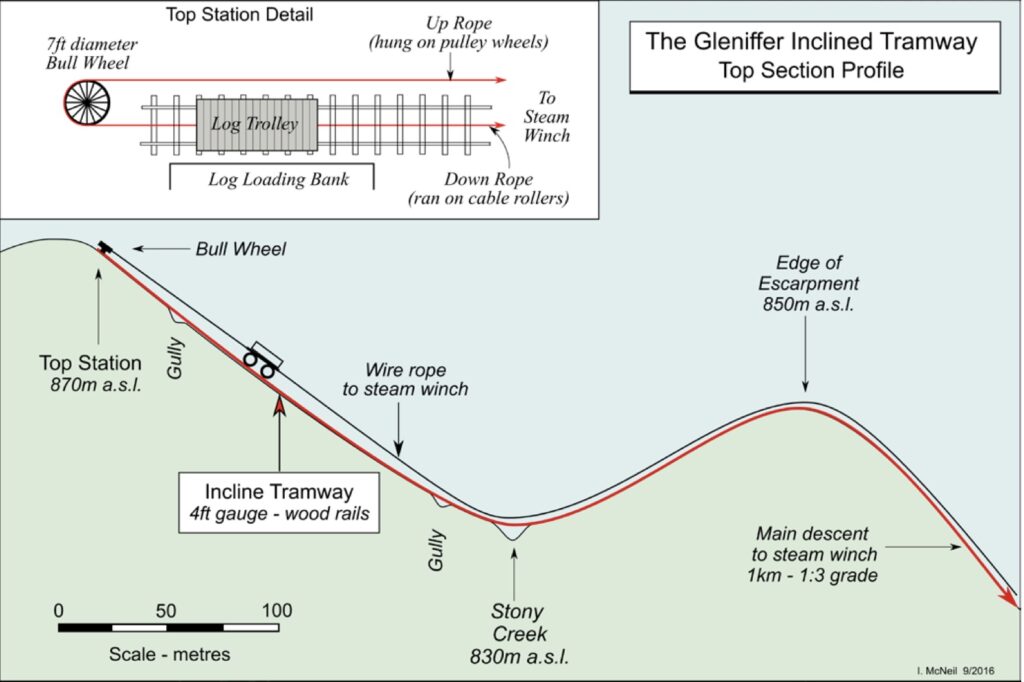

The initial survey, conducted in 1910, revealed the complexity of the undertaking. The route had to be straight, and the surveyors chose a long spur that dropped at a grade of about 1 in 3. Midway down, where the grade briefly levelled, the main ridge turned east, and the tramway continued straight down a secondary spur at even steeper grades. The line reached the valley floor just north of Buffer Creek near the settlement of Glennifer.

Construction and operation of the incline

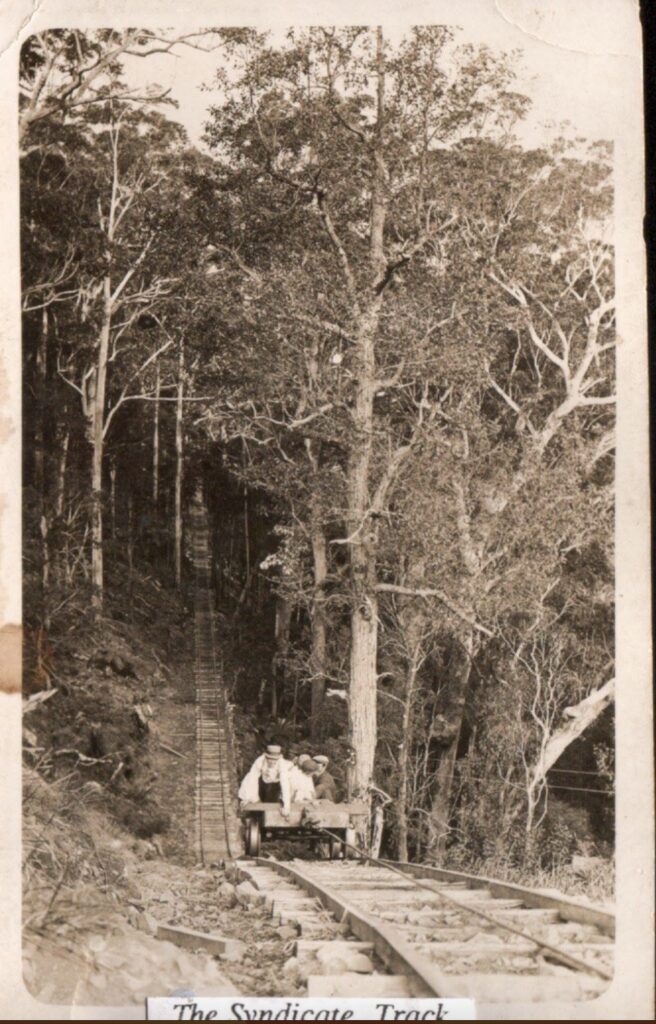

Construction of the tramway began in February 1911 under the supervision of George Smith, an experienced builder of incline tramways. To minimise earthworks, the line utilised shallow side cuttings. However, several trestle bridges and timber support work were required to maintain a manageable gradient. Thousands of rough posts, seven feet long, were driven into the ground to anchor the line securely to the mountainside.

The construction process was labour intensive and spanned two years. The tramway featured 4 x 3 inch timber rails cut from brush box, which were spiked to the sleepers. The first logs descended the incline in January 1913.

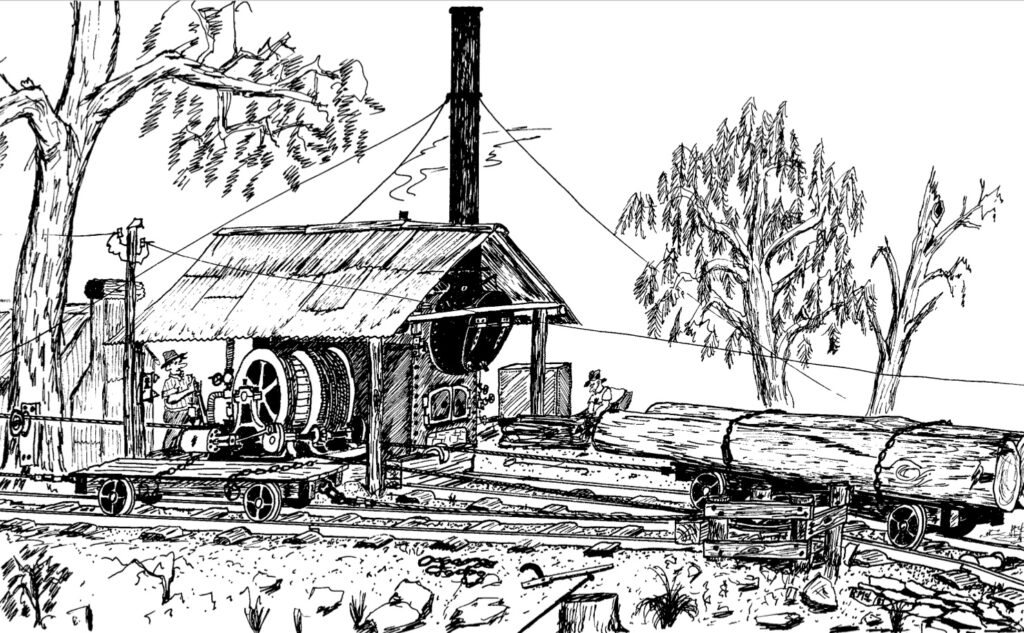

A 48-horsepower steam boiler and a double-drum steam winch powered the system. They were sited halfway up the line. The equipment was hauled up to the half-way site via a less steep route using two teams of bullocks yoked together, taking over four weeks and involving more than 40 bullocks.

Moving the six-ton boiler to the site posed a significant challenge. On the steepest sections, the wire rope from the boiler and its wooden sled was threaded through a pulley wheel a hundred yards above the bullocks, attached to a stout tree, then back downhill to the waiting bullocks who would heave downhill to lift the load yard by yard up the mountain. The alternate teams of bullocks had to be taken back down to the river flats every second day to pasture as there was no feed on the forested slopes.

The incline’s steepest section was the initial 1.1 miles, with gradients ranging from 1 in 2.5 to 1 in 3.5. This section included one of the larger trestle bridges. The grade then eased to 1 in 6, where the steam boiler and winch were located. The final 0.75-mile climbed at a gradient of 1 in 4.

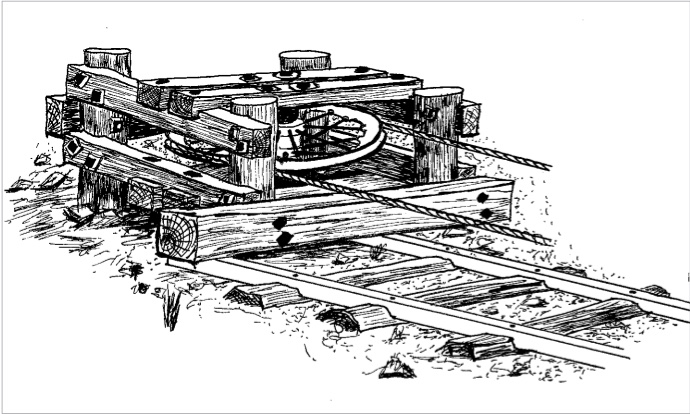

At the top of the incline, a seven-foot diameter bull-wheel was mounted horizontally. The wire rope from the steam winch drum ran along the tramline, suspended on pulleys hung from adjoining trees. It looped around the bull-wheel and returned down the centre of the tramline on cable rollers to hitch onto the top end of the top truck. Another wire ran from the bottom end of the top truck back down to the steam winch drum.

This interesting hauling set up was necessary because of the up and down nature of the top section of the line. The laden top truck had to be hauled to the escarpment’s edge before it headed downhill under gravity.

The bottom section was more conventional. A single wire rope from the winch’s second drum ran down the centre of the track on cable rollers to attach to the bottom truck. Raising the empty bottom truck acted as a brake for the descending laden top truck.

After bullocks hauled hoop pine logs from the forest to the top station, they were loaded onto the empty top truck. The operator then telephoned the winch driver, who communicated with the bottom operator before starting the winch. The two log trucks met at the steam winch, where the logs were off-loaded from the top truck onto the bottom truck.

The winch driver knew the location of the trucks below and above him by the number of coils of wire rope on the winch drum. Water for the boiler was supplied along a pipe from a rock ledge with seeping water.

The winch driver reversed the winch to bring the empty top truck back up and the loaded bottom trolley down. Both operators rode on the trucks.

The engine was located in a fairly level section of the line halfway up because the truck being hauled up to the top served as a brake to the other truck, bringing logs down the line. This was deemed efficient as it saved on power.

Every Sunday, the winch operator, Roy Humphries, had to climb up the line to the winch and light the fire so steam was raised and ready for operation first thing Monday morning. He stayed all week in the on-site two-roomed hut. He replaced the original driver, who quit after only two weeks, saying that one “needed to be related to the native bear tribe” to climb the precipitous mountain each week.

The first truck trip of the week conveyed the operators and timber workers from the bottom station including the fireman, both operators and the timber workers.

Initially, the logs were transported to Langdon and Langdon’s timber yard in Sydney, where they were processed and used to make furniture and cabinetry. They travelled six miles from the tramway along the Gordonville Road to the Bellinger River, where the BTCo built a wharf on waterfront land they leased. Bullock teams hauled the logs until the company purchased a 7-horsepower Fowler steam traction engine. From the river, punts took the logs to the river mouth at Urunga, where they were transferred to steamers for shipment.

After World War I, during the post-war boom period, the BTCo established a small sawmill near the bottom of the incline where the Gordonvale and Buffer Creek Roads met.

The challenges

The incline faced many challenges, including weather conditions. Wet weather caused landslides, like the significant one in April 1918, which required the construction of a 100-foot trestle bridge to span the gap within two weeks. Prolonged dry periods also created problems, as water for the boiler became scarce.

Maintenance was a constant issue, with trestle bridges and supports swaying under the weight of the laden trolleys.

Despite these challenges, the incline operated intermittently until the early 1920s. The rising costs of timber extraction, maintenance and labour, along with a decline in timber demand, strained the operation’s profitability.

The BTCo attempted to adapt by starting a sawmill at Glennifer. Work began on extending the tramway, including building a tunnel, to the mill, but the company never completed it. A survey to extend the top end of the incline to the headwaters of Wild Cattle Creek was also carried out in April 1918.

The Syndicate Tramway ceased operations in July 1922, and the following year the Langdon & Langdon timber yard in Sydney burnt down. While the Glennifer sawmill re-started in April 1924, the opening of the Dorrigo to Glenreagh railway in 1924 provided a more efficient route for timber transport, practically rendering the expensive incline obsolete. Enormous quantities of timber could leave the mountain for Coffs Harbour Jetty, which provided an all-weather deep sea port. In contrast, the Bellinger River was only navigable by shallow-draught vessels, and the Urunga Bar at the mouth of the river was notoriously dangerous for shipping.

In March 1929, the tramway and hauling plant were advertised for sale by auction, but there was little interest from buyers. The tramway remained unused until G L Briggs and Sons, pioneer sawmillers on the Dorrigo plateau, took over the company in August 1932.

The legacy

Today, the legacy of the Syndicate Tramway endures as a testament to the ingenuity and determination of the early timber industry pioneers.

While little physical evidence remains – scattered sleepers, lengths of timber rail, old pulley wheels and cable rollers, a log trolley, and the bull wheel – the story of the tramway is preserved through a walking track established by the local historical society. The track, as part of a 1988 Bicentenary Project, follows the old bullock track in the bottom section to the winch station and incline, offering visitors a glimpse into a bygone era of logging on the edge.

A great read and thank you for the vivid and informative narrative.

Just awesome to think of building and operating such an extreme means of transport. Thanks.

Great read and thanks to the local historical society for their continued input and support.

Hi, please ring me about sawmilling in that area. My great grandfather Joseph Reid had mills at Moleton, Dundarriban and Clouds Creek.

Kind regards

Glenn Reid 0412997343.

Good afternoon Robert,

Another story that is a testament to the intelligence, ingenuity and engineering skills of pioneering timber men.

A timber railway was built by sawmiller Lars Anderson in the Brisbane Valley. He constructed a number of them – three I believe.

I was fortunate to be involved with the recovery and salvage of a log trolley from one site with John Rasmussen, known to me as “Redcliffes”. The tramway was winch operated with an up and down trolley with a divergence where the loaded ‘down’ trolley passed the empty “up” trolley. As I understand, the system was purely gravity operated with a brake at the top for some speed control.

We took the wagon, which unfortunately had to be cut in two, and transported it to the “Woodworks Museum” at what was then the Qld Forestry complex. The wagon was restored and a working replica of the mechanism (albeit somewhat truncated) was built at the museum to demonstrate the methodology.

I am sure there is another story in the tramway that operated on Fraser Island with its unique steam engines.

Oh this has been so informative and to imagine what these men did to get that timber down the mountain, really extraordinary stuff.

Such creative ideas and ingenuity and hard work including the bullocks.

Great part of the history of this area.

Hello Robert. Thankyou for a great read, well done.

Robert, a well researched and written article, we owe a lot to our pioneers. I know my great, great uncle was one who invested in the Syndicate.

Thank you for keeping history alive for us.

Another very interesting read about the pioneers of the country and how they managed to achieve what they did under horrendous circumstances. Amazing! Thankyou Robert.